Topic: Performance Management

Performance Management

This page features information on performance management for TAM. Whether you are selecting performance measures, monitoring performance-based data, or monitoring improvements, you will find what you need here.

Overview:

Implementation Considerations:

Related Subsections:

Performance Management 2.2.2

Asset management utilizes performance management to set objectives, define measures, establish targets, and monitor results. Transportation Performance Management (TPM) relies on the TAM principles and process to help achieve the agency's broader goals and objectives.

Relationship to Federal TPM Activities

The MAP-21 Act (2012) established a performance-based program intended to focus Federal Aid highway program and public transportation system (e.g., bus, light rail, and ferry) investments on national transportation goals. It was also intended to increase accountability and transparency in the use of federal transportation funds, as well as improve project decision-making through the strategic use of system performance information. The performance-based provisions of MAP-21 were retained in the FAST Act in 2015.

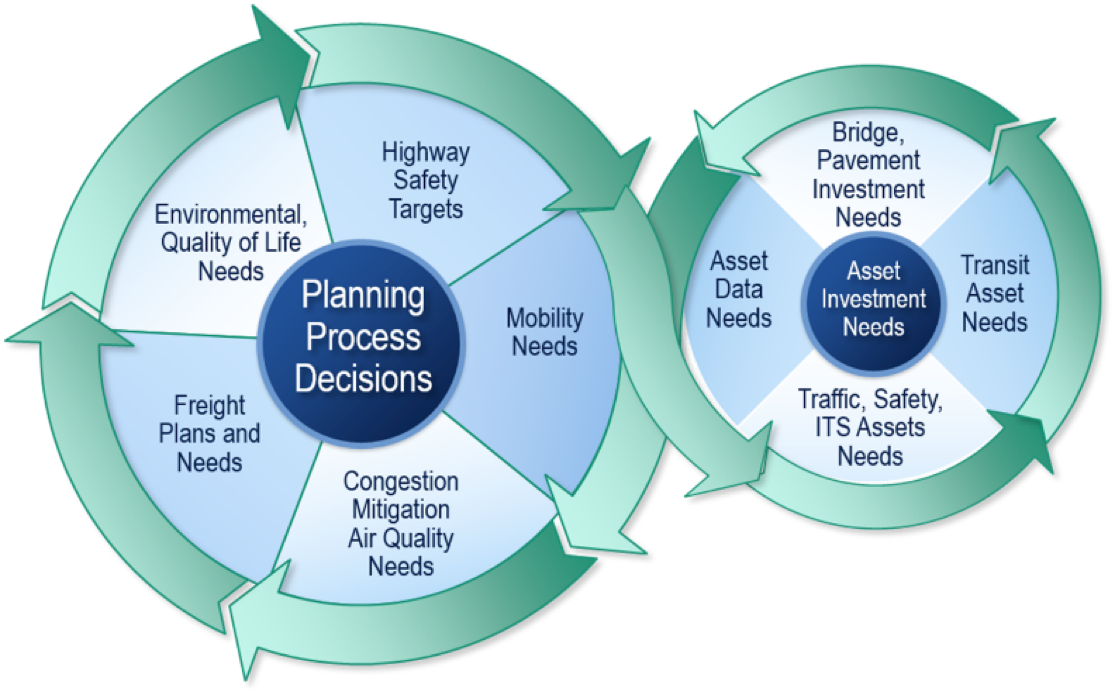

TPM is defined by FHWA as a strategic approach to making investment and policy decisions to achieve national performance goals using system information in accordance with rules established by the Department of Transportation (see Figure 2.3). The FHWA recognizes asset management as the application of TPM to manage the condition of infrastructure assets needed to provide for mobility and safety in the nation’s transportation system. In short, the FHWA refers to asset management as the engine driving infrastructure performance.

Figure 2.3 FHWA's Strategic Approach to TPM

Source: FHWA TPM Homepage. 2019 https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/tpm/

Asset management plans document the processes and investment strategies developed by an agency to manage its infrastructure assets. These asset management plans support an agency’s performance-based planning and programming processes for making long-term investment decisions and feed shorter-term project and treatment selection activities. Together, these activities ensure the investment decisions of an agency are aligned with performance objectives and goals.

TPM Regulations

The TPM provisions for highways included in federal law are implemented in accordance with rulemakings organized around the following six elements:

- National goals – focusing the Federal Aid highway program on the seven areas listed below:

- Congestion reduction

- System reliability

- Environmental sustainability

- Freight and economic vitality

- Infrastructure condition

- Reduced project delivery delays

- Safety

- Measures – assessing performance or condition in carrying out the TPM-based Federal Aid highway program

- Targets – funding recipients are required to document future performance expectations under a fiscally-constrained environment

- Plans – identifying strategies and investments for addressing performance needs

- Reports – documenting progress toward target achievement and investment effectiveness

- Accountability and transparency – requiring federal funding recipients to achieve or make significant progress toward targets

TPM Relationship with TAM

There is a close relationship between TPM and TAM, since both consider asset and system performance, risks and available resources to achieve desired objectives over time. Both rely on a strategic approach, using data to make investment and policy decisions in order to achieve performance objectives. Internationally, there is less distinction between asset management and performance management, with the IAM defining asset management as encompassing the “balancing of cost, opportunities and risks against the desired performance of assets to achieve the organizational objectives.” In the United States, TAM applies to the technical and financial decisions, plans and actions related to physical infrastructure, while TPM considers a broad range of system performance categories.

A graphic illustrating the integration of asset management and performance management is provided in Figure 2-4. In the figure, the circle on the left represents the interconnection of the various performance areas that transportation agencies are concerned with throughout their planning processes. Flowing into the performance circle is the asset management circle, representing an agency’s infrastructure needs to support system performance.

The FHWA’s Expert Task Group (ETG) published a white paper explaining the relationship between asset management and performance management. It acknowledges the performance of a transportation system is dependent on many factors, including operational characteristics, and system usage and demand, in addition to the physical condition of the infrastructure assets. The paper explains that “performance management focuses on how policies, resource allocation, and other decisions affect all aspects of system performance including safety, operations, environmental stewardship, and infrastructure condition.” (FHWA 2019) Asset management is described as an application of performance management principles with a long-term focus to manage the performance of infrastructure assets, the resources allocated to operate a transportation system, and the investments made to achieve the agency’s long-term goals and objectives.

Figure 2.4 Integration of Performance Management and TAM

Source: NHI 136106A, Introduction to Transportation Asset Management. 2019

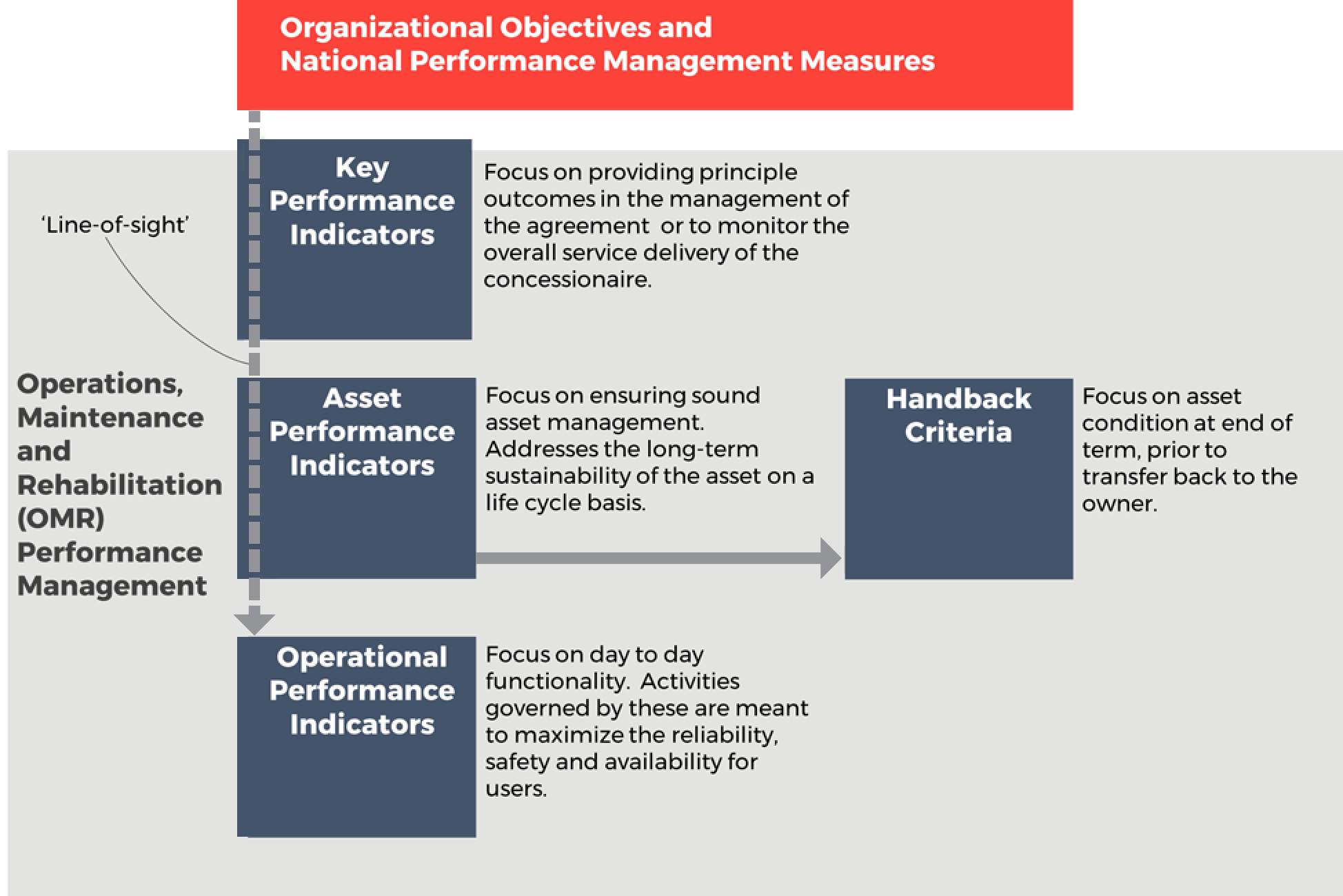

British Columbia

To support the alignment of agency policies, objectives and day-to-day practices, the Province of British Columbia established the tiered structure shown in Figure 2.5 for a design-build-finance-operate project. The highest of the three levels, Key Performance Measures, defines the high-level outcomes for service delivery in terms of a few key strategic areas. The second level, Asset Preservation Performance Measures, defines the minimum acceptable condition levels for each of the individual assets to preserve their value. The third level, Operational Performance Measures, corresponds to the many specific requirements for operating and maintaining the highway in a safe manner on a day-to-day basis. The tiered approach helped align stakeholders at all levels and clarified priorities for all parties.

Performance Management Framework

To support the alignment of agency policies, objectives and day-to-day practices, agencies may establish a tiered performance management framework, such as the example illustrated below for a model Design-Build-Finance-Maintain-Operate (DBFMO) project (Figure 2.5). The highest of the three levels, Key Performance Measures, defines the high-level outcomes for service delivery in terms of a few key strategic areas. The second level, Asset Preservation Performance Measures, defines the minimum acceptable condition levels for each of the individual assets to preserve their value. The third level, Operational Performance Measures, corresponds to the many specific requirements for operating and maintaining the highway in a safe manner on a day-to-day basis.

Further discussion on Performance Management Frameworks, defining Performance Measures and Performance Targets is included in Chapter 6.

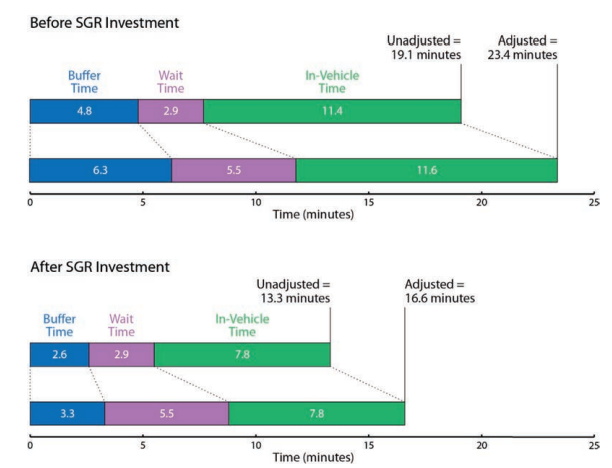

For the transit community, TCRP Research Report 198 presents a framework for developing relationships between service quality and asset conditions, using a variety of transit system performance and customer satisfaction attributes. The research conducted in developing the report found many correlations between asset condition and performance, as noted below (Spy Pond Partners, et.al, 2018).

- Asset condition is related to the quality attributes of Frequency, Reliability, and Travel Speeds. As assets decline in condition, failures become more likely, reducing frequency, reliability, and average speeds.

- Asset condition is related to Appearance/Aesthetics in that customer perceptions of this factor are likely to be worse when assets are in poor condition and/or are technically obsolescent.

- Asset condition is related to other service quality attributes, including Comfort, Ease of Access, Environmental Impact, Information, Safety, and Security. For these attributes, increasing asset failures may affect quality, although the effects may be difficult to model. For instance, reduced service frequency resulting from increased failures can lead to greater crowding and less comfort. A particularly challenging area is safety. Given that operating severely deteriorated assets could compromise safety, in theory and in general practice, transit agencies establish thresholds for safe operations and remove an asset from service, rather than operating unsafely. Thus, potential safety issues tend to become operational issues, rather than actual safety issues. Regardless, customer perceptions are likely to be worse when assets are in poor condition for these factors, as in the case of Appearance/Aesthetics.

In one example, the impact of State of Good Repair (SGR) investment on the calculation of Effective Journey Time (EJT) is demonstrated. The example illustrates the differences in the calculated unadjusted and adjusted journey time, both before and after SGR investment, for a hypothetical rail line. Although the calculation is not based on actual data, it is intended to show that, after a SGR investment, both the adjusted and unadjusted journey times decrease. Before investment, the actual journey time for all components is 19.1 minutes, increasing to 23.4 minutes when adjustment factors are included. Following an investment in improved vehicles and track, these journey times decrease to 13.3 and 16.6 minutes. Looking closer at the components of time that change in this example, the decrease in buffer time after SGR investment indicates that travel times are more reliable and passengers do not have to build in as much buffer when planning their trips. Overall, in this example, SGR investments reduce EJT an average of 6.8 minutes per trip. This savings can be multiplied by an average value of time and number of trips per year to yield a prediction of the annual user benefit resulting from the investment. The results can be used in a variety of ways to analyze asset conditions and service quality.

Minnesota DOT

The Minnesota DOT’s performance management system consists of clear policies, performance trend data and performance forecasts to guide investments and operational decisions. The system is designed to (http://www.dot.state.mn.us/measures/):

- Address stakeholders’ desire for accountability and transparency

- Provide more informed decision-making and solutions to increasing challenges

- Enhance customer-responsiveness

- Ensure compliance with legislators' mandates

- Improve internal management

- Facilitate refinement of programs and services

- Set benchmarks for comparison of results

MnDOT uses performance criteria to guide capital investments and annual operational budgets. Transportation system and agency performance reports are regularly reviewed by MnDOT management. The ongoing measurement and review process assists MnDOT in evaluating the efficiency of service delivery and assessing the effectiveness of program activities. This objective-based approach increases transparency, and encourages innovation by keeping the focus on outcomes.

The accountability and transparency provided by MnDOT’s performance management system has contributed to MnDOT’s reputation among elected officials as a trusted partner in addressing challenging issues.

Accountability and transparency are a foundation of success for public agencies. The benefit is increased trust. This can help elected officials view MnDOT as a trusted partner and work together on challenging issues. Confidence in agency decision-processes and results is important to legislators considering new investments.

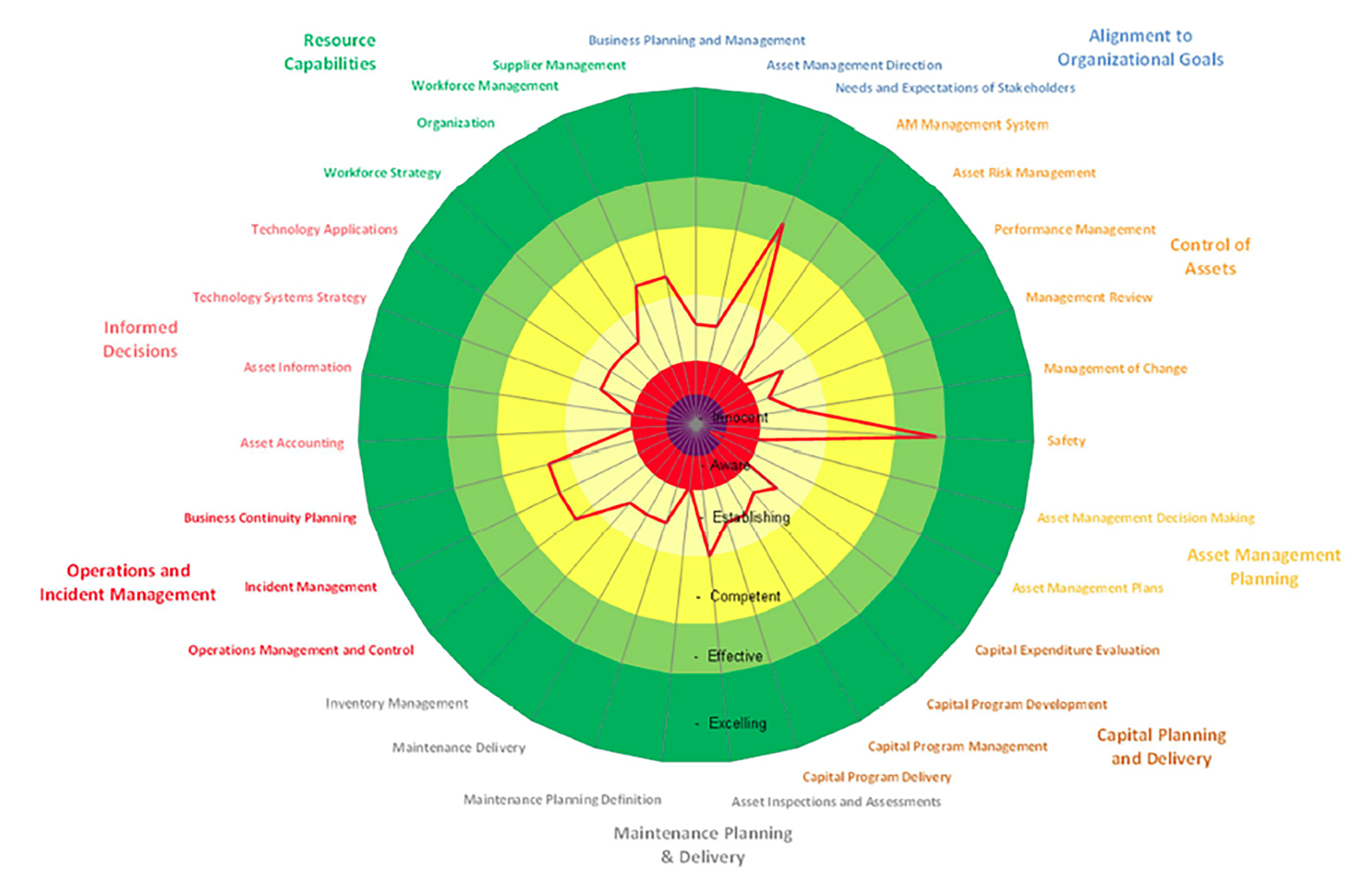

Assessing Current Practice 2.3.1

An assessment of current agency competency against industry-leading practice enables an agency to assess a desired future performance level. It can also help to identify the steps required to reach that goal.

TAM is an evolving process; ongoing improvement is an important component for a TAM program. In fact, the ISO 55001 Asset Management certification requires ongoing assessment and continual improvement.

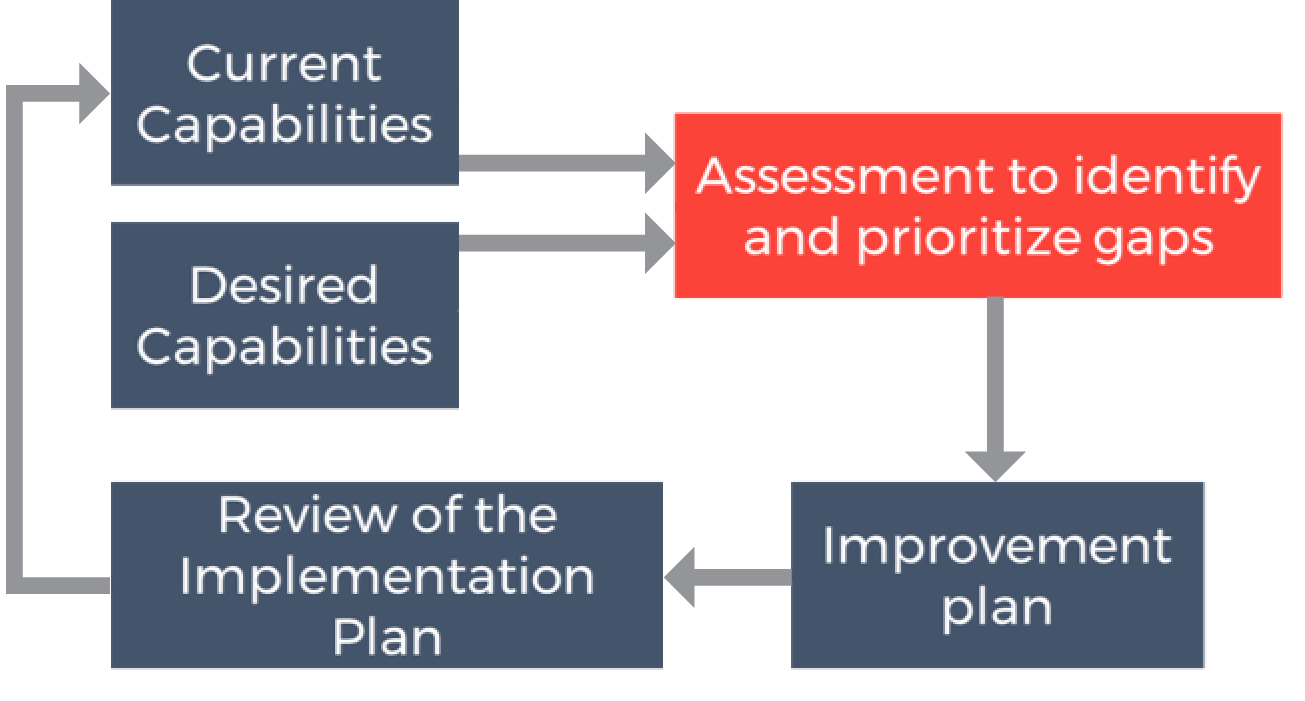

A gap assessment process is used to understand how well an agency aligns with an established asset management framework. The gap assessment can be conducted internally or by a third party. Organizations seeking or wanting to maintain ISO certification will also undergo a formal third party audit.

The results of a gap assessment can help agencies identify changes in business processes needed to better link plans and decisions and better align to leading practice.

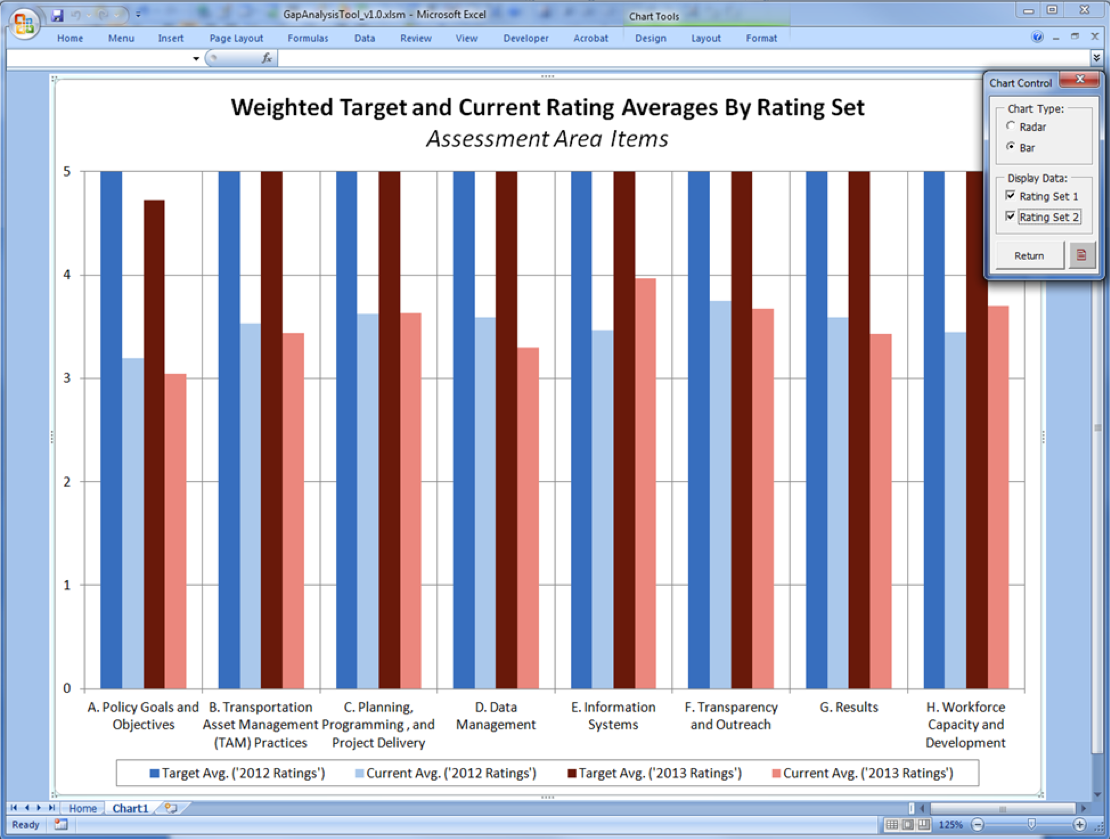

NCHRP Project 08-90 led to the development of a gap analysis tool, available through AASHTO and the TAM Portal. Figure 2.8 illustrates how this assessment tool is intended to be used. There are several other frameworks that can be used, including ISO 55001 and the Institute of Asset Management (IAM). A range of gap assessment framework’s are discussed further in Table 2.1. Each framework, process or tool will enable an agency to assess current performance and, from this, identify a desired capability level.

Figure 2.8 TAM Improvement Cycle

Source: Modified from original in NCHRP Project 08-90

TIP

Factors to consider when prioritizing advancement in TAM approaches will vary from agency to agency. Consider those factors that are of most importance to you and are well-aligned to your strategic goals.

In some cases, agencies also seek benchmarks that reflect how peers are performing to help them decide on the level of maturity and complexity to which they should aspire. ISO 55001 trends away from this. It encourages agencies to check against a framework of practices and process, and select what is best for the agency. Chapter 6 addresses benchmarking and related topics.

Actions to close gaps between desired and actual performance should be addressed within a TAM improvement or implementation plan.

Undertaking a gap assessment can form an important part of a change management process by aligning those within the agency on current performance, opportunities and targets for improvement.

Table 2.1 - Frameworks for Assessing Current Practice

| Framework | NCHRP 08-90 Gap Analysis Tool | ISO 55001 Asset Management Gap Analysis | International Infrastructure Manual (IIMM) | IAM Self-Assessment Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background | This tool was developed based on the tool and process created through development of the 2011 AASHTO TAM Guide. Uses a point scale for evaluating current and desired capabilities. See more | This is the most widely adopted standard for asset management globally. It is generic to accommodate many contexts. Describes a management system approach to asset management. See more | Recognizing that the ISO Standards for asset management are very much the “What to do”, the IIMM looks to provide the “How to do it”. Identifies an Asset Maturity Index (Aware, Basis, Core, Intermediate, Advanced) to identify the current and an appropriate level of asset management for each asset. See more | As an aid to the application of ISO 55001, the IAM decided to update their methodology into one that enables organizations in all sectors to measure their capabilities against the requirements of both PAS 55 and ISO 55001. See more |

| Assessment or Focus Areas |

|

|

|

|

| Why use this framework? | This framework is best for an agency that wants to work explicitly within a US-defined context that adopt wider influences. Since this tool can be fully customized by an agency, an agency that wants to tailor the analysis to their particular needs will find this useful. Finally, the tool facilitates the analysis of data, and can generate graphs and charts using the data imported into it. | This framework is ideal for agencies that want to adopt a world-recognized approach to asset management that provides a developed asset management lexicon. This is currently the most internationally-recognized standard in the world. | This framework has been refined over time with many examples that illustrate successful application of concepts by organizations. Public agency focused, and largely written for the asset management practitioner responsible for civil assets. | This standard is well recognized internationally, is infrastructure agnostic, and has applicability to infrastructure owners in both the private and public sector. It has many other resources developed along with the framework including training materials, reference guides and courses to upskill an agency. |

Amtrak

In 2016, Amtrak Engineering undertook an Asset Management Capability Assessment which bases maturity on the degree of formality and optimization of processes. The assessment uses several questions grouped into eight assessment areas, which describe operational processes necessary for asset management success. This maturity methodology is aligned with emerging guidance from the Institute of Asset Management (IAM), ISO 55001 standards, and requirements of the US FAST Act.

The assessment used a six-point scale, scoring Amtrak at the Establishing level, indicative of an agency that is actively developing asset management capabilities and establishing them to be consistent, repeatable, and well-defined.

Based on the 2016 assessment results, key challenges were identified and a series of improvement recommendations were developed and integrated into an Asset Management Improvement Roadmap.

In addition, Amtrak established a target position, driving process implementation priorities, with the intention of continuous monitoring by repeating the capabilities assessment process on an annual basis.

2016 Amtrak Asset Management Capabilities Assessment Results

Source: Amtrak Engineering 2019

Defining and Prioritizing Improvement in TAM Approaches 2.3.2

Agencies managing different types of assets are faced with the decision of where to prioritize advancing formal asset management. Determining where to improve the organizations effort can depend on different factors, but should always align with the organizational context and priorities.

TAM Webinar #61 - TAM Innovations

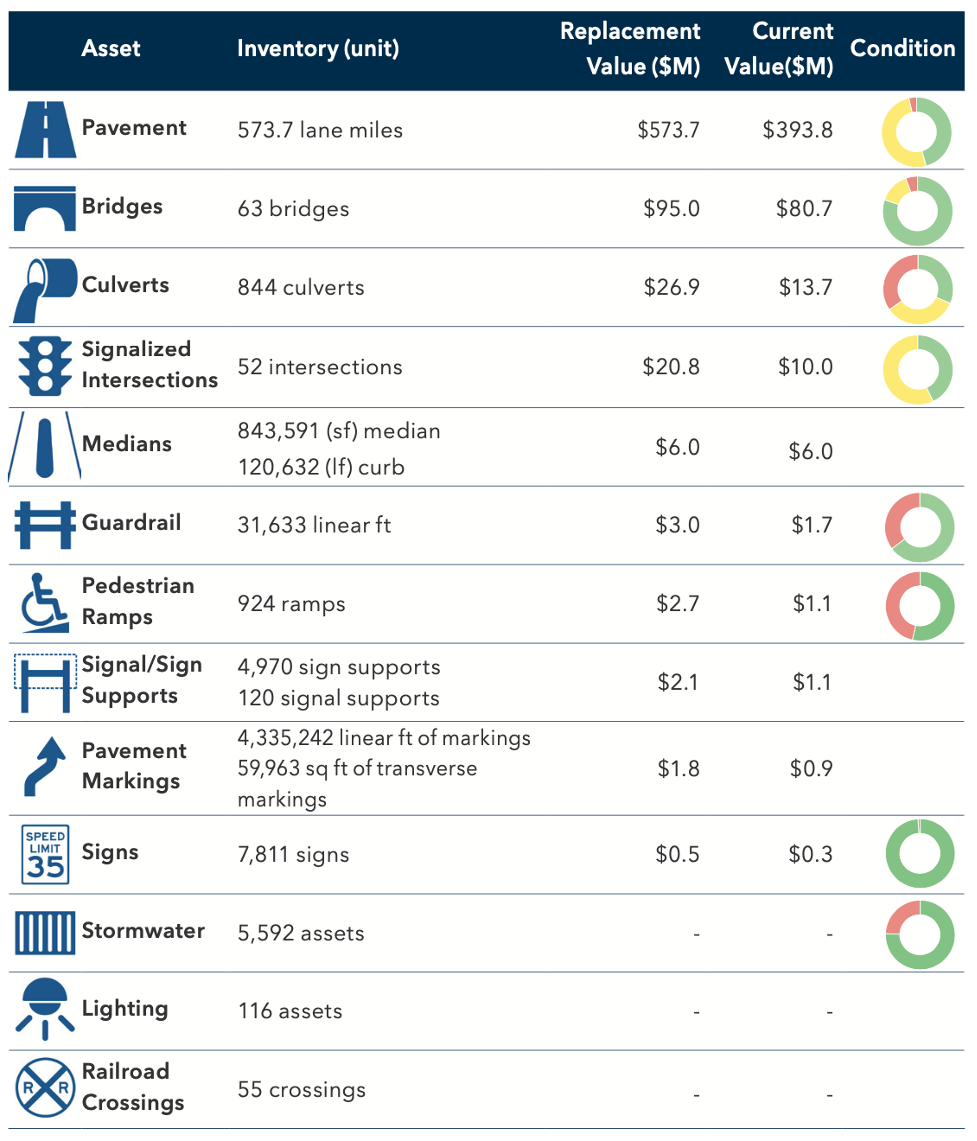

For transportation agencies, asset management typically begins with the high-visibility, high-value assets, such as pavements and bridges. However, operating the transportation system requires a supporting cast of assets, typically referred to as ancillary assets, that include lighting structures, roadway signs, ITS assets or even operations facilities and technology hardware components. Establishing the appropriate management approach, and future desired approach for each asset is an essential step in strategic planning for asset management, defining boundaries around the effort. Furthermore, for each type of asset, it is important to determine how broadly to define the inventory of assets, such as the decision to include only arterial roads initially or all roads in a network.

Defining Appropriate Management Approaches for Different Asset Categories

An appropriate approach to manage and monitor each asset governed by the TAM framework needs to be established. Depending on the nature of the asset and the level of risk involved, different approaches can be selected by an agency.

Structuring asset management also involves evaluating different management approach- es and defining the appropriate level of maturity. There are several approaches to managing highway assets, each with different data needs, and several ways to structure and implement asset management processes. These include:

- Reactive-Based. Treatment is performed to fix a problem after it has occurred.

- Interval-Based. The asset is treated based on a time or usage basis whether it needs it or not.

- Condition-Based (Life Cycle Approach). Select intervention based on a forecasted condition exceedance interval.

Chapter 4 provides more details on these different approaches to managing assets.

Processes and approaches can range in their level of detail and complexity. This is what forms the foundation of some asset management maturity levels. Much like deciding on the scope of assets to manage, the level of advancement of the asset management processes an agency adopts should depend on the context and readiness of the agency, as well as the problem being addressed. Consideration should be given to the data, processes and tools available to support the asset management approaches and processes, as well as resource availability and capability. It is common for an agency to begin at a simple level and mature over time towards more complex asset management that integrates processes and decision-making.

Utah DOT

To accomplish the objective of allocating transportation funding toward the most valuable assets and those with the highest risk to system operation, UDOT developed a tiered system of asset management. Asset Management tiers range from one to three with tier one being the most extensive management plan for the highest value assets.

Tier 1. Performance-based management

- Accurate and sophisticated data collection

- Targets and measures set and tracked

- Predictive modeling and risk analysis

- Dedicated funding

Tier 2. Condition-based management

- Accurate data collection

- Condition targets

- Risk assessment primarily based on asset failure

Tier 3. Reactive management

- Risk assessment primarily based on asset failure

- General condition analysis

- Repair or replace when damaged

Source: Utah DOT. 2018. Utah TAMP. https://www.tamptemplate.org/tamp/053_utahdot/

Prioritizing TAM Improvements

Deciding on the appropriate management approach and level of asset management is a strategic decision that should consider several factors:

Organizational Strategic Goals

The decision of which assets to prioritize should be driven by the organization’s strategic goals. A desire to focus on one aspect of the transportation system over another in order to meet a larger objective can present a good reason for prioritizing some assets over others.

Asset Value

A common consideration for selecting assets to include is the financial value. Monetizing value provides a consistent way of comparing asset classes. In general, assets that are the most expensive to replace or cause the greatest financial concern for an organization fall into the highest priority. Strategic management of these assets means strategic investments over the life cycle of the asset, which will prevent or delay the need for significant additional investment, help avoid premature failure, and allow time to plan for appropriate replacement.

Data Availability

TAM as a concept is heavily dependent on data. Deciding on which assets to focus on based on existing data collection and management practices and will often support achievement of “quick wins.” Data availability does not always indicate strategic priority or risk exposure of the asset, but can still be an important factor in selecting assets to include the cost of collecting and analyzing data to form the basis for more advanced TAM decision making can in some instances be significant, and require new skills and training.

It should be recognized that data does not need to be comprehensive and complete as a basis for TAM decision making. An accepted approach is to group assets into classes (age, type, function) and then inspect a sample set. This can provide important insights to guide long-term planning at minimal initial expense/time. It can also highlight any issues with particular types of assets and allow for more detailed inspections to be undertaken if required. A gap analysis to define future data requirements and determine how to collect this data should be considered for long term TAM outcomes.

Risk of Failure

Often, it can be necessary to consider including assets if the probability and consequence of failure is significant. Assets with a high risk of failure can be a high priority due to the potential losses to the agency and its stakeholders should they fail. Asset management can alleviate or prevent the impact of failure.

Asset Criticality and Network Reliability

Decisions to formally manage certain assets can be based on their importance to the service provided, such as operations, or the importance of the travel paths under consideration. Defining criticality is context specific, but is important, since user experience is based on the journey, not the specific assets. Considering criticality in selecting assets to include in TAM will ensure that the most important assets–those necessary to maintain network reliability–are managed first.

Stakeholder Influence

In general, the scope of TAM should be agreed to in coordination with leadership and influenced by stakeholders. Stakeholders can be any asset owners, metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs), cities, tolling authorities, P3 concessions, federal (mandated requirements), and others. The public can also be stakeholders who influence which assets to include, especially when high-profile incidents potentially attributed to the state of good repair occur.

Aurizon

Aurizon is Australia’s largest freight rail operator, transporting more than 500 million tons of coal to markets including Japan, China, South Korea, India, and Taiwan, in addition to over 800 million tons of freight through an extensive network throughout the country. Aurizon Network manages the largest heavy haul rail infrastructure network in the country. The network is economically regulated by the State through a process that sets investment levels and tariffs. Asset management practice is well-entrenched in the organization, with a focus on “optimizing the life of assets, keeping a tension between investment in maintenance and capital.” The scope of the Aurizon Network asset base, known as the Regulated Asset Base includes all assets used in the provision of the rail infrastructure service. Management is informed by external engineering standards and legislative and regulatory obligations including:

- Prevention and intervention levels specified in an Asset Maintenance and Renewals Policy.

- Commitments to the Central Queensland Coal Network.

- A Safety Management System aimed to minimize safety risks.

- Network Strategic Asset Plan models which are based on asset age, predicted condition and historical and forecasted usage.

Source: Aurizon. 2019. Network: Planning and Development.https://www.aurizon.com.au/what-we-deliver/network#planning---development

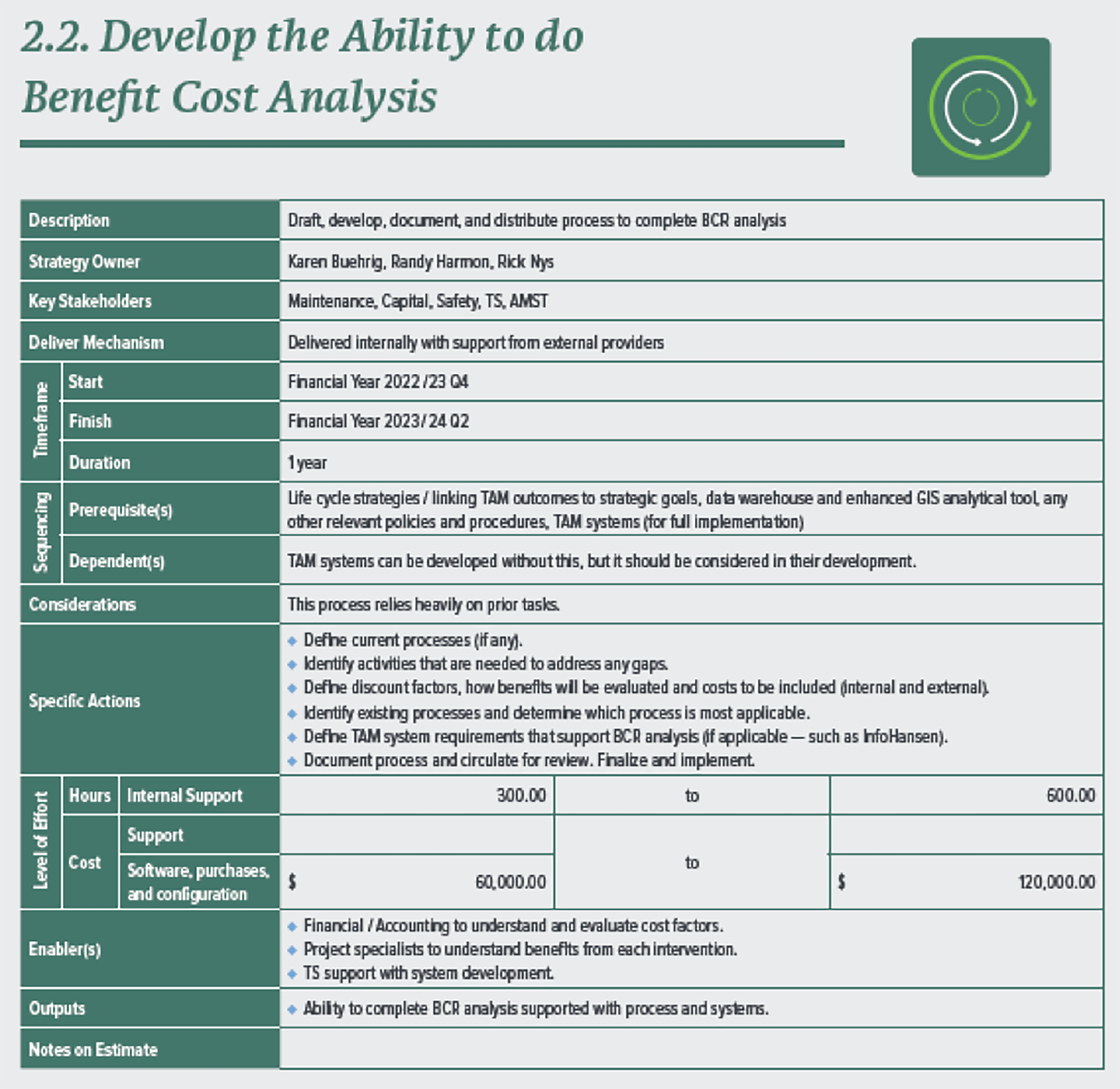

Developing a TAM Implementation Plan 2.3.3

A TAM implementation plan can clearly communicate an agency’s next steps for TAM and define responsibilities for implementation.

TAM Webinar #39 - TAMP Implementation

The product of a gap assessment will often take the form of an implementation plan for TAM improvements. These improvements can involve changing behaviors across many business units within an organization. The actions should, therefore, be prioritized and staged to advance one step at a time. When defining actions, it is important to understand the purpose and outcome to be achieved, who is responsible, how long it will take and how many resources are required for it to happen.

Note that a TAM Implementation Plan is different from a Transportation Asset Management Plan (TAMP) described further in Section 2.4. An implementation plan focuses on business process improvement, while a TAMP focuses on an organization’s assets and how it is investing in and managing them. However, the implementation plan may be included as a section of a larger TAMP.

The improvements identified need to recognize potential barriers to implementation. As an example, improving decision-making tools will likely require improvements in data practices. The implementation plan should consider any foreseeable obstacles, including staff resistance to new business procedures, lack of support from agency leadership, inadequate skills among staff, data integration issues or outdated analytical tools.

Communicating the Implementation Plan

Effective, organization-wide communication can serve as a powerful tool to facilitate smooth and swift adoption of the TAM implementation plan. At the start of implementation, communicating the future vision and benefits can help build awareness and buy-in. Throughout the duration of the implementation initiative, communication about milestones and accomplishments can help sustain or regain momentum. Additionally, as different projects are initiated, delivered and completed, agencies will want to ensure that the resulting changes in processes, systems and tools are adopted and used consistently to achieve the intended outcomes and objectives. As illustrated in Figure 2.9, the TAM communication strategy should cover six key elements – why, who, what, when, how and how well.

Objectives. Why communicate?

Establishing early buy-in to the implementation plan by providing an upfront explanation of why execution of the TAM implementation plan is needed—the anticipated benefits for the organization as well as for different stakeholder groups—will help jumpstart success of the implementation.

Stakeholders. Who delivers and receives the communication?

To make sure the right people are receiving the right information, it is key to develop and categorize a complete list of internal and external stakeholders who will be impacted by the TAM implementation plan and its resulting changes. In determining stakeholders, consider who needs to receive different types of information and who best to deliver that information to support achievement of implementation plan objectives.

Messages. What are the messages to communicate?

In developing the key messages to communicate, consider intent – what should stakeholders know, think or do as a result of the message? Key messages should promote awareness, desire and reinforcement of the implementation plan and its associated changes. They should also align with objectives of the implementation plan as well as organizational objectives.

Timing & Frequency. When will the communication occur?

Communication about the TAM implementation plan and corresponding changes should be timely, frequent enough to keep stakeholder groups well informed about approaching milestones and key dates of impact, and not so frequent that they lose value. Take into account what is being communicated and to whom, as different stakeholder groups receiving different types of messages often require different delivery frequency.

Tactics & Channels. How will information be communicated?

Depending on the duration of the TAM implementation plan and the number of associated changes, communication needs often shift over the course of its execution. Agencies should determine the most effective types of communication and delivery channels as they progress through change. By including stakeholder categories, messages and frequency as inputs when determining the most effective channels, the communications strategy remains agile, which facilitates continuous improvement.

Continuous Improvement. How well is the communications strategy working?

Assessing the effectiveness or performance of any strategy is important for achieving objectives. Including a stakeholder feedback loop into the communications strategy is one way to accomplish this. Agencies can use surveys, polls, focus groups or meetings to gather information and gauge opposition and support. This crucial feedback serves as guidance for subsequent content and can lead to changes in the communications strategy.

Figure 2.9 Communicating the Plan

Key questions to answer in communicating your implementation plan.

Clackamas County DOT

Based on their gap assessment, Clackamas County Department of Transportation and Development established a Transportation Asset Management Strategic Plan (TAMSP), which documents its methods to implementing a comprehensive transportation asset management program over a five year period. This TAMSP was accompanied by an asset management implementation strategy that identified the key actions to be undertaken.

Clackamas County, 2051 Kaen Road #426 Oregon City, OR 97045

Extract from Clackamas County DOT Implementation Plan

Monitoring TAM Program Improvements 2.3.4

Measuring TAM improvement is important for understanding if the plan needs adjustment, and to communicate success and motivate those responsible for implementation.

Once a commitment to make improvements has been made, the improvement process needs to be managed and monitored.

Regular updates, meetings, performance tracking (monitoring improving performance against the selected framework) and scheduled reviews by the TAM Governance Groups will help provide oversight to those responsible for undertaking the improvements.

This process also helps remove roadblocks by involving leaders from across the organization.

When to Re-Assess Performance

A regular commitment to monitor progress is important. This assessment will compare progress from the initial benchmark toward the desired level of competency. There is no set recommendation for when to assess progress; some agencies find it more important in the early stages of implementation, while others do not.

When considering the timing of progress assessments, it is important to consider:

- Process checkpoints. The frequency could be aligned with reporting requirements, but should also consider appropriate points where progress will be noticeable.

- Commitment. Undertaking an assessment will take time and resources, so it is important this is balanced against progressing with implementation.

- Champions and change agents. As these individuals are critical to the overall success of TAM implementation, if they change or need to monitor their own performance, then a review of progress can help motivate and reset goals.

Measuring Performance Improvements

Monitoring performance of the asset management system and the results of improvement actions can be challenging, as the cost of service delivery, quality of service levels and risk of service failures may shift over time, and can change following the implementation of an improvement action. The IIMM suggests some of the following potential TAM system performance indicators:

- Financial performance

- Data management performance

- Timeliness relative to target response times

- Productivity and utilization of resources

- Skills availability relative to planned requirements

- Adherence to quality procedures

Chapter 6 provides more information on performance measures, targets, and monitoring asset performance. Self assessment can focus both on service / asset outcomes experienced by users, as well as be internally focused to determine how well the agency is aligned with desired practices. It is important that agencies consider and select the appropriate level and focus of self-assessment for their requirements.

TIP

TAM Maturity Assessments should end with an Improvement Program, highlighting areas for self-improvement, which can then be prioritized according to agency priorities or strategic direction.

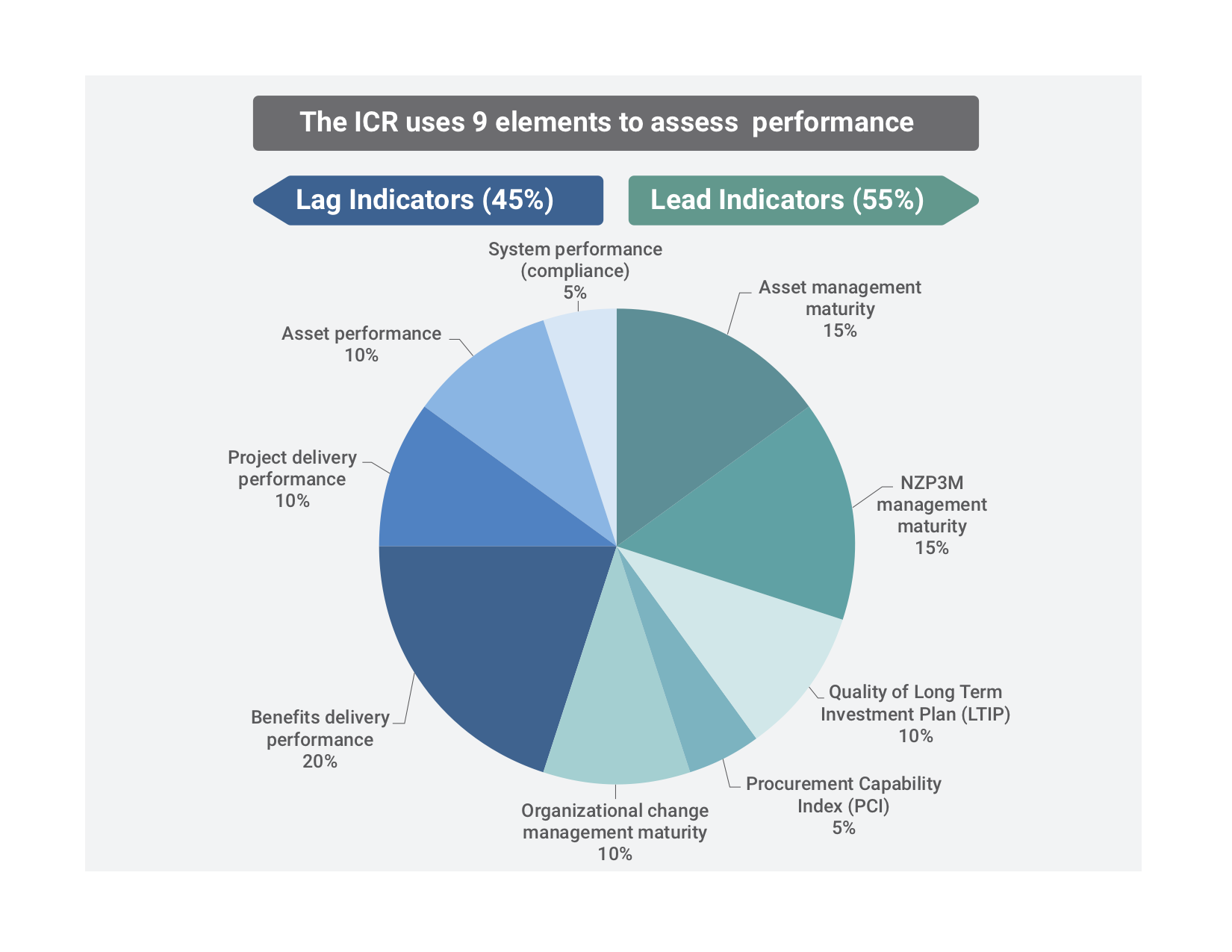

New Zealand Transport Agency

The New Zealand Treasury stewards the NZ government’s Investment Management System to optimize value from new and existing investments and assets for current and future generations of New Zealanders. One of the tools the system uses is the Investor Confidence Rating (ICR), which illustrates the confidence that government leadership (i.e. Ministers) can have in an agency’s ability to deliver investments that produce the desired results.

The ICR also promotes and provides a pathway for capability uplift. One element of the ICR evaluates the gap between current and target asset management maturity levels on the basis that good asset management practice provides the foundation for good investment management. The Treasury recommends periodic self-assessments using a methodology based on international asset management guidelines and the ISO 55001 standard.

The ICR assessment is conducted every 3 years, resulting in more decision-making autonomy for agencies that obtain a good rating and potential flexibility over investment assurance arrangement.

Adapted from New Zealand Treasury. Investor Confidence Rating (ICR).

https://treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/state-sector-leadership/investment-management/review-investment-reviews/investor-confidence-rating-icr

Defining Asset Service and Performance Levels 4.1.2

Before asset performance can be managed, an agency must first define what it is seeking to achieve. In TAM, asset performance is most commonly defined in terms of asset condition or maintenance level of service. Performance may also be evaluated in terms of safety, availability, reliability, resiliency and other service attributes. Regardless of the method used to monitor performance, it should be used to inform analysis that supports decisions to help ensure that investments enable an agency to achieve its goals cost-effectively.

Establishing Desired Levels of Service

Before a whole-life strategy can be developed and implemented, an agency must determine what they seek to achieve. In many transportation agencies, the desired level of service (or asset management organizational objectives, in ISO 55000 terminology) provides the linkage between what the goals of an agency are, and what investments and interventions should take priority when managing assets. High level goals should directly influence investment choices when resource allocation decisions are made. Service levels help establish when gaps need closing to achieve a goal, and merits investment. Chapter 2 discusses ways to create linkages between goals and investment decision making.

When managing the life cycle of existing assets, performance targets are commonly established as a way to manage service levels for the transportation network. How to determine the expected level of performance may vary depending on the type of asset being managed. Level of service targets that are part of performance framework typically are a mixture of both customer focused performance measures, and technical service measures that help those responsible for the asset assess what types of interventions might be required and when. Customer focused service measures are important to road users and other stakeholders that require mobility. Travel time reliability, safety, load capacity and clearances, and lane availability are all examples of service targets that are customer focused. Condition, strength, regulatory compliance and examples of technical service attributes are commonly of greater interest to asset stewards than asset users. Both types are service level targets that are important to evaluate the efficacy, effectiveness and efficiency of a transportation system.

TIP

“The organizational objectives provide the overarching context and direction to the organization’s activities, including its asset management activities. The organizational objectives are generally produced from the organization’s strategic level planning activities and are documented in an organizational plan.” (ISO 55000, 2.5.3.4) These organizational objectives are analogous to strategic objectives typically found in long range transportation plans.

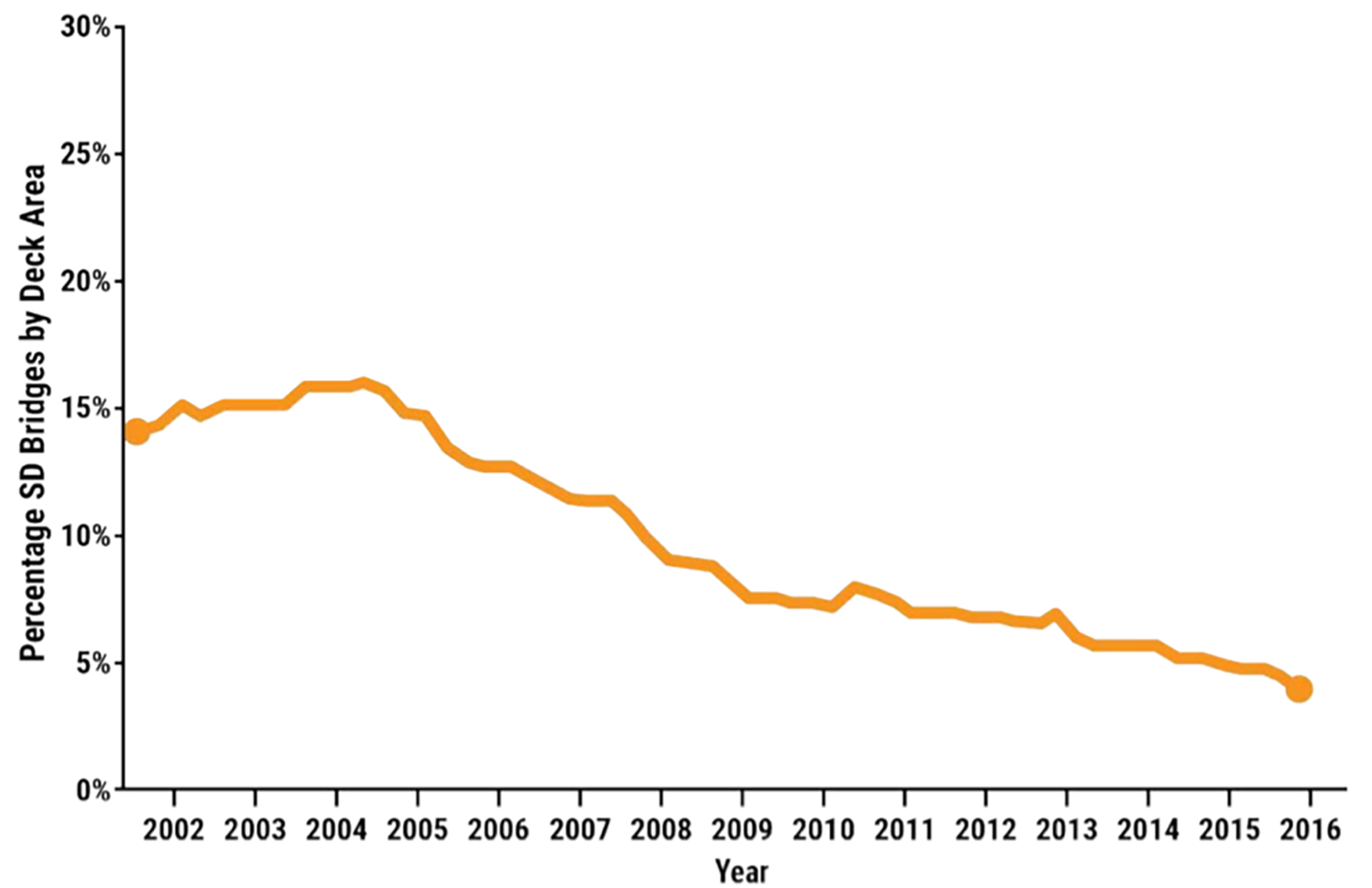

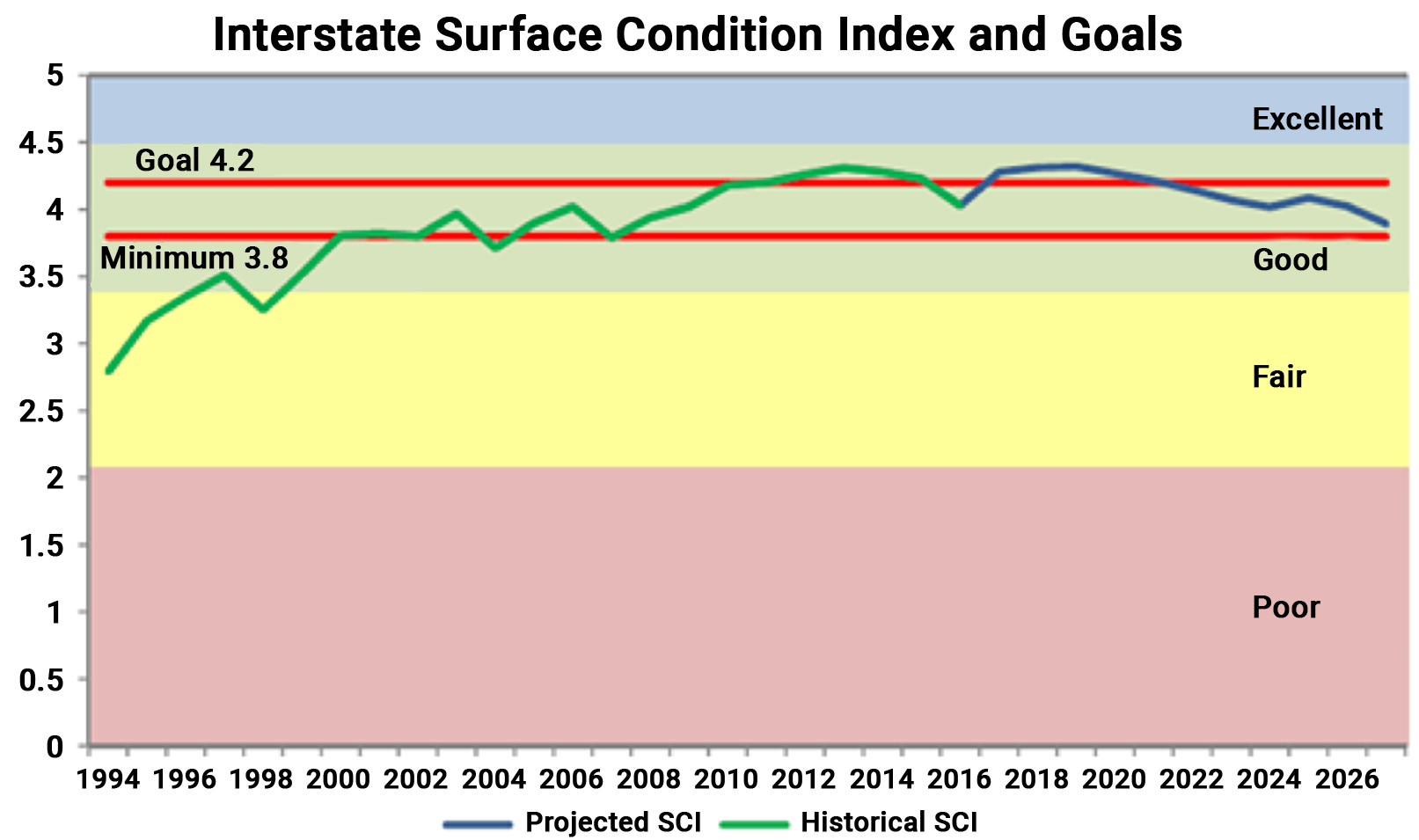

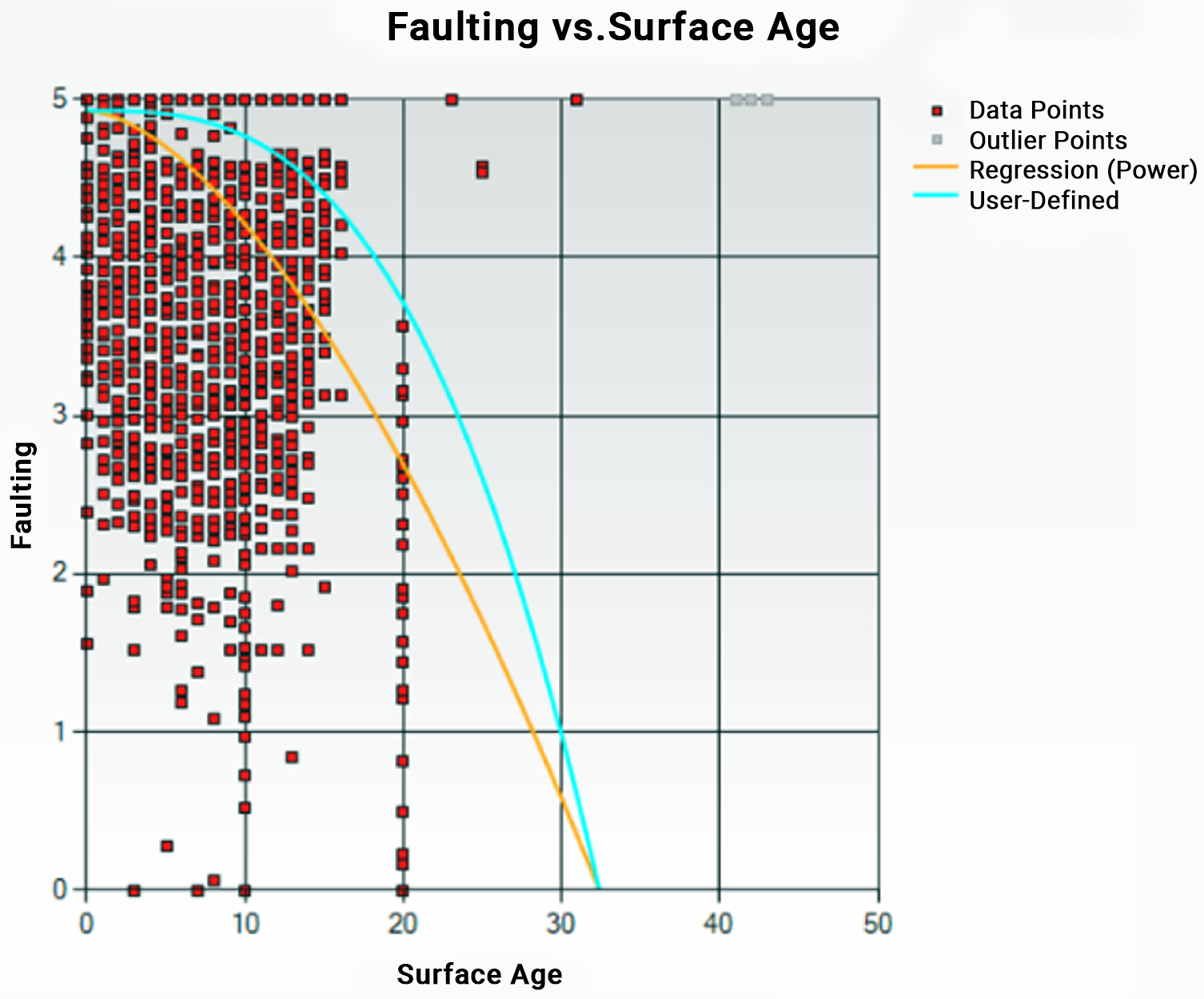

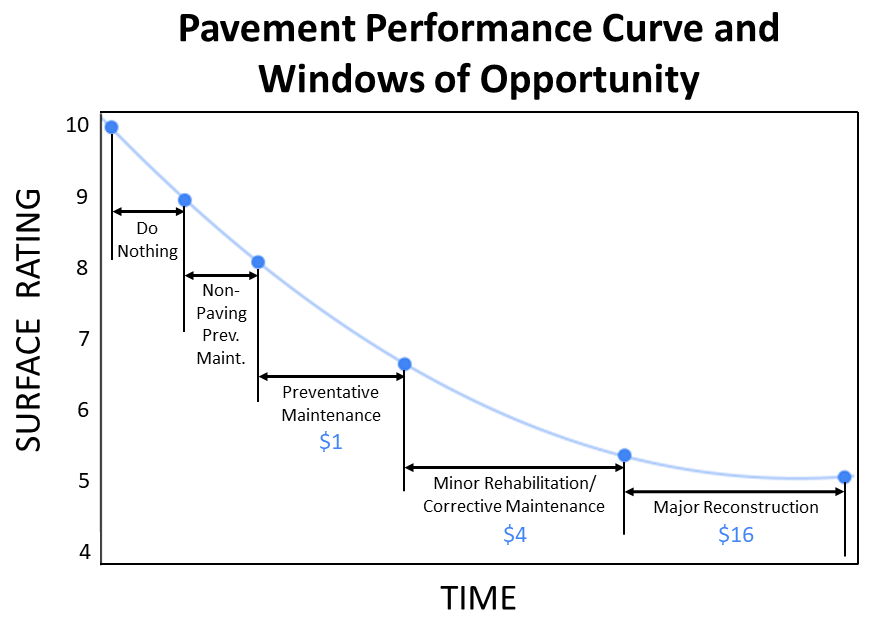

For pavements and bridges, and other assets managed using a condition-based approach, asset condition is commonly used to establish expected technical levels of performance, but also is relevant to customers. For example, condition is employed as a proxy in this way for pavements because it is objectively measurable, deterioration has some predictability. It is a valuable service attribute because often, user experience is also directly connected to condition as well. Potholes, rutting and roughness all reduce quality of service from a pavement. Performance measures, such as those discussed in Chapter 6, are used to establish the desired long-term performance and to set short-term targets that can be used to track progress towards the long-term objectives. For other highway assets, including those managed using interval- or time-based maintenance approaches, performance may be linked to the expected service life, the ability of the asset to fulfill its intended function, and/or other operational factors. For these other highway assets, performance targets are often established as part of a Maintenance Quality Assurance (MQA) program in terms of desired maintenance levels of service (MLOS) and integrated with operational service targets that may also be customer focused.

Risk can also be used as a measure of performance. As described in chapter 2, risk considers both the potential impact and consequence of failure. This can be particularly useful when the potential consequences of failure impact other assets or facilities. An example of how Colorado uses risk to manage rockfalls is included in section 4.3 of this chapter. Additional details on how to track risk-based performance measures is included in Chapter 6.

Establishing a desired level of performance is typically a collaborative process that considers existing conditions, available funding, expected demands on the system, policy goals and guidance, and stakeholder priorities. The desired level of performance is typically established once baseline data is available, so performance trends can be evaluated. The desired level of performance may be adjusted over time to reflect changes in agency performance, changes in asset condition, capacity, safety, resiliency and other factors.

Three types of service expectations are often used in combination to manage asset performance:

- Performance target – the level of performance beyond which additional performance gains are not desired or worth the additional cost. When performance is measured based on condition, the desired performance may describe the desired state of good repair. There may be an expected specific time frame to achieve this desires performance target.

- Current Performance – an intermediate level of performance achieved by the organization and is usually reported relative to the desired target. Target setting is described in more detail in Chapter 5.

- Minimum acceptable performance – the lowest level of performance allowed for the asset or asset class to still function as designed.

Performance expectations may be set for the road network, a road corridor, for individual assets or for a group of assets. Commonly, performance expectations are set using a combination of asset class or subclass or sub network, such as:

- Key network corridors.

- Bridges on the National Highway System.

- Interstate pavements.

- Culverts larger than 10 feet in diameter.

- Traffic signals serving more than 10,000 vehicles per day.

TIP

A desired state of good repair is often established as the level of performance beyond which further performance gains are not necessary or desirable, usually represented as a condition state for a set of assets.

The nature of performance expectations can be either strategic or tactical or operational. Strategic expectations support freight movement; for example, the long-term goal of providing unrestricted flow of legal loads is supported by a performance expectation of no load-posted or restricted bridges on interstate highways. This expectation cannot be accomplished without the tactical delivery of work to address factors contributing to the physical condition of bridges. Thus, an agency may include tactical expectations to perform maintenance and repair on structural members on a routine basis or as conditions warrant. These enhancements can be also integrated with renewal and other rehabilitation interventions to help improve both tactical performance metrics, as well as achieve higher level goals and objectives. Operational improvements such as more responsive snow clearance, and better signage are all integrated treatment options to achieve the strategic objective.

Life cycle management analysis, and the decisions it supports, require service levels, performance targets and other objectives to be able to determine the optimal choices for agencies to select during resource allocation. Over an asset life cycle, a range of interventions are possible, from reactive, routine and preventative maintenance, to large investment associated with renewal, replacement, or removal. Having targets helps select the right interventions and investment option while balancing risk, service and cost.

Connecting performance measures to higher level strategic goals also supports an agency’s ability to communicate how technical measures relate to system performance as experienced by highway users and other external stakeholders, thus tying asset management outcomes to system performance. Asset management measures are often very technical. Performance indicators like bridge ratings, pavement distress measurements, and risk ratings are not commonly understood by those outside transportation agencies. However, agencies can use these technical measures to support the performance indicators that are more commonly understood and prioritized by system users and external stakeholders. Communicating system performance and the status of the road network is discussed in Chapter 2, and is illustrated in several examples below. Customer service level targets are often established for this purpose, and give users an ability to understand the quality of service they should expect on the transportation system.

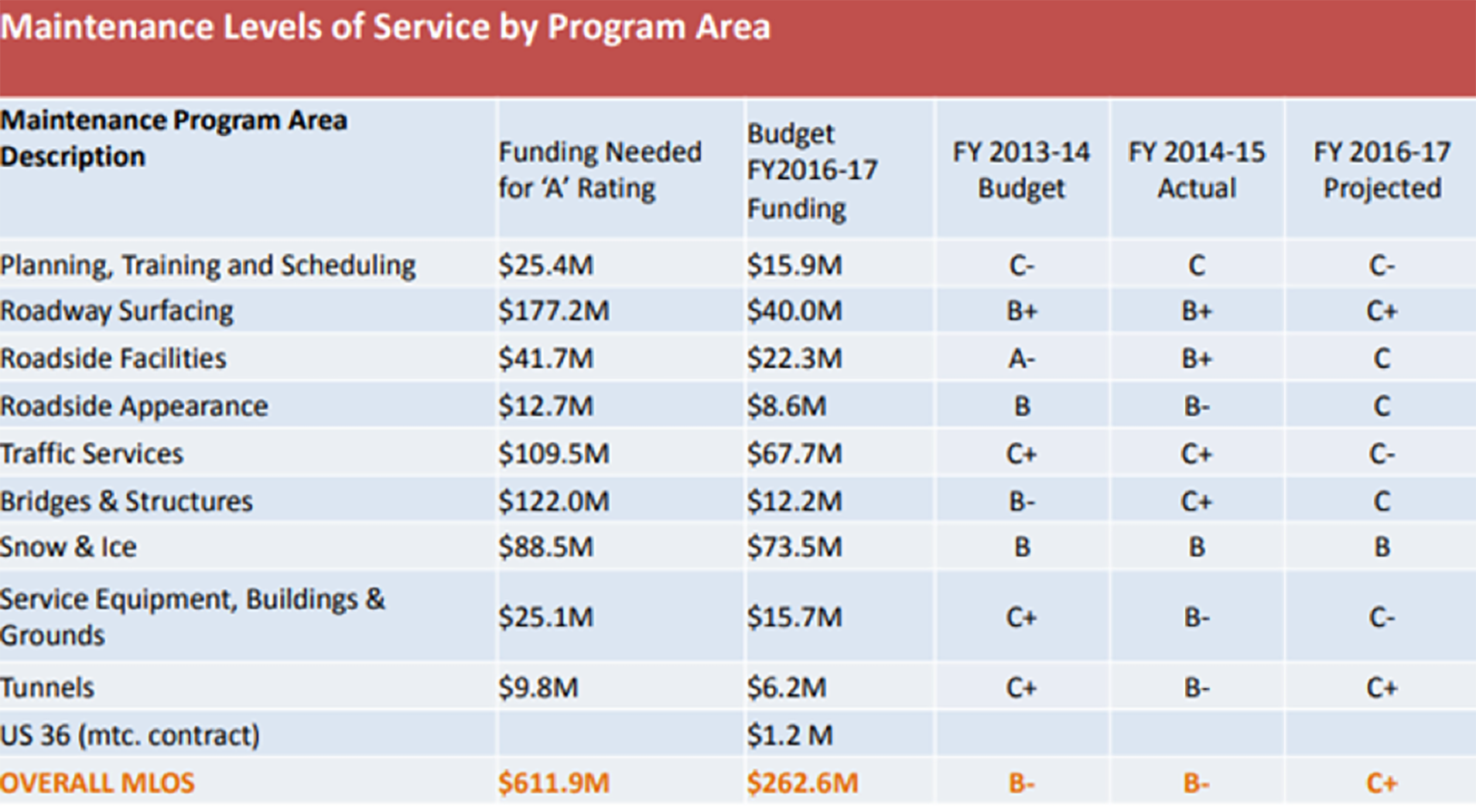

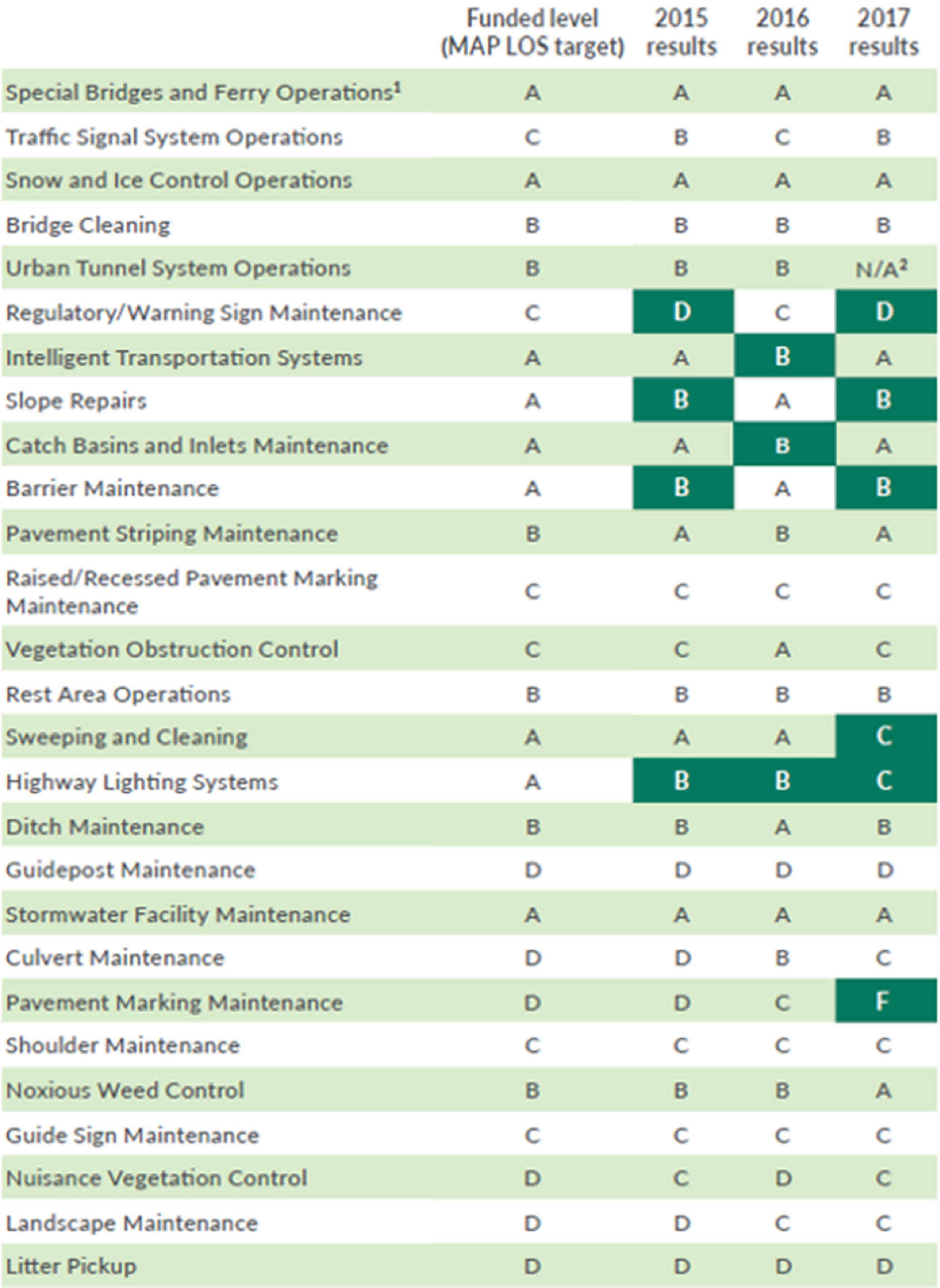

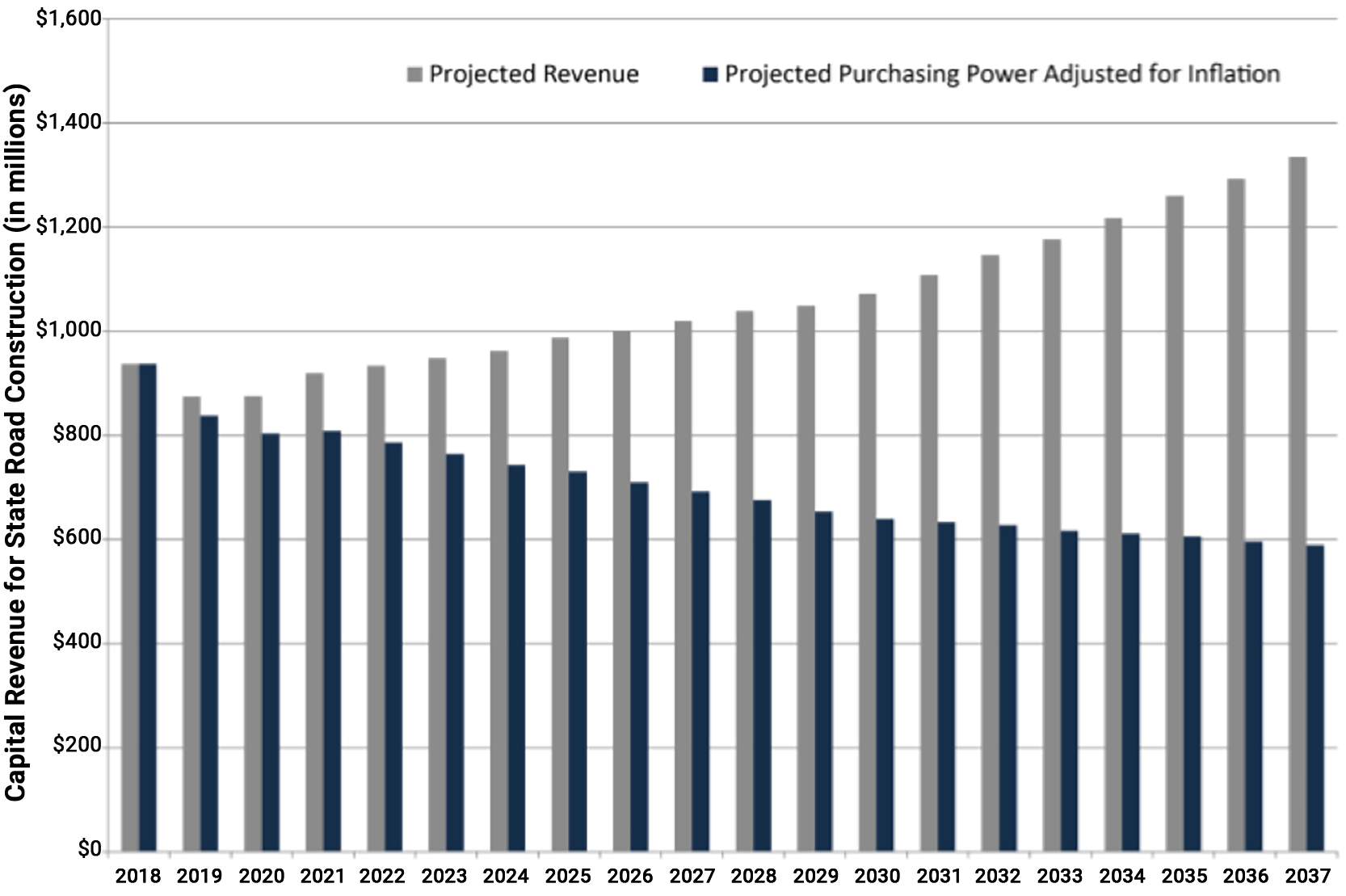

Colorado DOT

Each year, the Colorado DOT must report to its legislature on the statewide highway infrastructure and the agency’s ability to meet those needs with available resources. This requirement is met through the Annual Infrastructure Deficit Report, which addresses pavements, bridges, and annual maintenance. The agency supports the annual maintenance portion of this report with its Maintenance Level of Service Measure, which rates the delivery of services in nine program areas in terms of a letter grade from A to D and F. The agency has used historic data to develop deterioration rates for each service area that estimate the resources needed to improve the maintenance level of service by a given amount over a specific time period. These estimates are summarized in the Report, which is in turn used by the Legislature and the DOT to establish the annual maintenance budget. The figure provides an example of information on MLOS in the 2016 Report. Once the targeted MLOS is established, maintenance funding can be allocated to ensure that agency priorities are met.

Colorado DOT Example of Funding Needed to Support Maintenance Levels of Service

Source: Colorado DOT. 2016. https://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/cdot_smart_2017_presentation.1.pdf

Washington State DOT

When seeking to establish the connection between investments and performance across a wide range of assets or roadway attributes such as litter, vegetation height, drainage, or functionality it is helpful to relate all of the various measures of performance to a common rating scale. Washington State DOT has developed its Maintenance Accountability Process to establish the relationship between maintenance level of effort and the resulting level of service. The process rates conditions and services in seven areas using a common letter-grade system, or MLOS.

- Roadway Maintenance & Operations.

- Drainage Maintenance & Slope Repair.

- Roadside and Vegetation Management.

- Bridge & Urban Tunnel Maintenance and Operations.

- Snow & Ice Control Operations.

- Traffic Control Maintenance & Operations.

- Rest Area Operations.

Each group of services or conditions includes several performance measures, which are translated to the MLOS grades of “A” (highest performance), “B”, “C” (adequate performance), “D” or “F” (unacceptable performance). Applying the MLOS grades allows for a consistent means of rating performance across services and geographic regions. Letter grades can also be represented in photographs of facilities that meet the criteria for each condition state to support communications with stakeholder groups. The MLOS are outcome-based measures that allow the agency to predict the expected level of service that can be achieved based on anticipated budget and work planning decisions. By tracking maintenance expenditures and MLOS results annually, Washington State DOT is able to adjust its maintenance priorities and budgets to address system needs and stakeholder wants.

Source: https://www.wsdot.wa.gov/Maintenance/Accountability/

New Zealand Transport Agency

New Zealand Local Government Act legally requires councils to consult with their communities on their long-term plans. The consultation plan provides an effective basis for public participation in infrastructure decision-making associated with the long-term plan. It includes a fair representation of overall objectives, and how tax levels, debt, and levels of service might be affected by the intended plan and can be readily understood by interested or affected people. The Auditor General recently reviewed plans produced by communities across the country. Key findings highlighted aspects that help define good practice:

- Consultation documents present their information in a concise, readable and understandable way.

- Clear and unambiguous explanations on why proposed taxation and debt increases and significant changes in plans or intentions were considered “affordable” or “equitable” make consultation documents more effective.

- Some communities used a road-trip analogy throughout the document. The analogy makes technical subjects relatable without over-simplifying the issues.

- Some used a personalized approach that connected with people. For example, one uses two primary school children, Maia and Xander, who are pitched as the “champions of the Long Term Plan 2018-2038.”

By focusing on the inclusion of transportation customers, New Zealand municipalities are better able to address customer needs, inform customers of the actions they are taking, and refine work planning practices to address concerns critical to infrastructure operations and customer expectations.

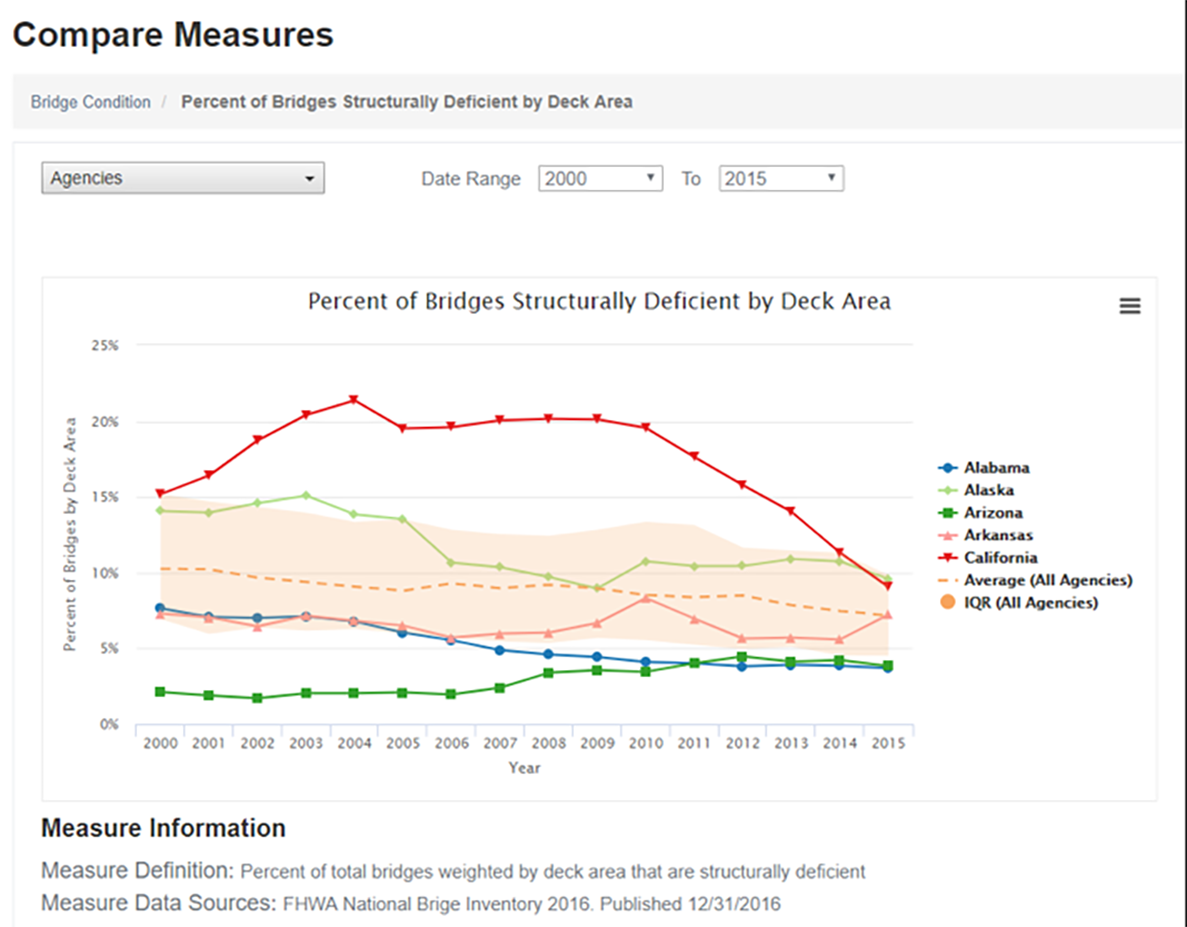

Selecting and Using Performance Measures 6.1.1

This subsection discusses the importance of using performance data to make decisions. It highlights the role of performance measures and provides suggestions on selecting effective measures to meet agency needs. This section also introduces innovative new performance measures that agencies may consider in the future. A more detailed discussion of Transportation Performance Management can be found in Chapter 2.

Performance Management Framework

As discussed in Chapter 2, transportation agencies have embraced the use of performance data to drive investment decisions. A performance-based management approach enables agencies to select and deliver the most effective set of projects for achieving strategic objectives, while also improving internal and external transparency and accountability.

A typical performance management framework includes:

- A clear idea of the agency’s strategic objectives.

- The use of performance measures to assess performance.

- Methods to evaluate and monitor performance results.

- The evaluation of factors with capacity to improve long-term performance.

- The allocation of funding to achieve agency objectives.

- Ongoing processes to monitor and report progress.

A fundamental component of the framework is the use of performance measures to evaluate system performance and the importance of establishing business processes to evaluate, monitor, and use the data to influence agency decisions. These are achieved by aligning decisions at all levels of the organization with the agency’s strategic objectives and ensuring that the right performance measures are being used to drive decisions. This alignment helps to ensure that resource allocation decisions and the day-to-day activities of agency personnel support the agency’s priorities and the interests of external stakeholders.

The existence of a regular, ongoing processes to monitor and report results is critical to identifying and implementing improvements to system performance or to further the effectiveness of the performance management process. The continual monitoring and update of a performance management framework is reflected in Figure 6.1, which illustrates inputs to performance targets and how ongoing monitoring and adjustments are fed back into the framework to adjust future targets. The surveys conducted regularly to support a pavement, bridge or maintenance management system are examples of the types of performance monitoring activities fundamental to an effective performance management organization.

TPM Webinar #16 - Caltran's Performance Management Framework

Agencies with a performance management framework in place have benefited from:

- Maintaining a clear and unified focus for making agency decisions based on agency priorities, public input and available resources.

- Using available funding more effectively to preserve or improve system performance while lowering life cycle costs.

- Allocating available resources based on analysis of past performance and expected conditions to address areas most in need of attention.

- Having the data to confidently defend funding requests or explain the impact of reduced budgets.

- Building a transparent and accountable organization by communicating the basis for making resource decisions.

- Meeting legislative requirements.

TIP

It is important to select performance measures that are meaningful to the agency and that can directly inform decisions. This may vary depending on the agency context, culture, and TAM maturity.

Arizona DOT

In 2001, during the development of a long-range transportation plan (LRTP), the Arizona DOT took a strategic approach to how investments should be made. Under the new approach, Arizona DOT established the following three investment categories:

- Preservation, including activities that preserve existing transportation infrastructure.

- Modernization, including improvements that upgrade the efficiency, functionality, and safety without adding capacity.

- Expansion, including improvements that add transportation capacity by adding new facilities or services.

To implement the new initiative, the Arizona DOT developed a report titled “Linking the Long-Range Transportation Plan and Construction Program” or "P2P Link” that applied financial constraints to the long-term vision. Through a collaborative process that involved a consultant, local and regional governments, and transit agencies, the Arizona DOT published an implementation plan for putting the P2P Link into practice. The resulting process includes scoring projects based on both a technical and policy score that are added together to determine a project’s ranking. The technical score is generated by the asset owner based on an analysis of the data while the policy score is determined based on each project’s contribution to LRTP goals and performance measures. The process helps to ensure that projects are ranked in accordance with the agency’s strategic objectives using only the most meaningful criteria in a transparent and defensible way.

Arizona DOT’s Link Between Strategic Objectives and Investment Decisions

Source: ADOT. 2014. Linking the Long-Range Plan and Construction Program P2P Link Methodologies & Implementation Plan.

https://azdot.gov/sites/default/files/2019/08/p2p-methodologies-implementation.pdf

Performance Measures

Performance measures are used within a performance management framework to allocate resources and provide feedback on the effectiveness of the activities in achieving overall objectives. Performance measures are indicators used for evaluating strategies and tracking progress. A performance measure can be an indication of asset condition, such as a pavement condition rating, or an indication of an operational characteristic, such as the annual number of fatalities on a facility.

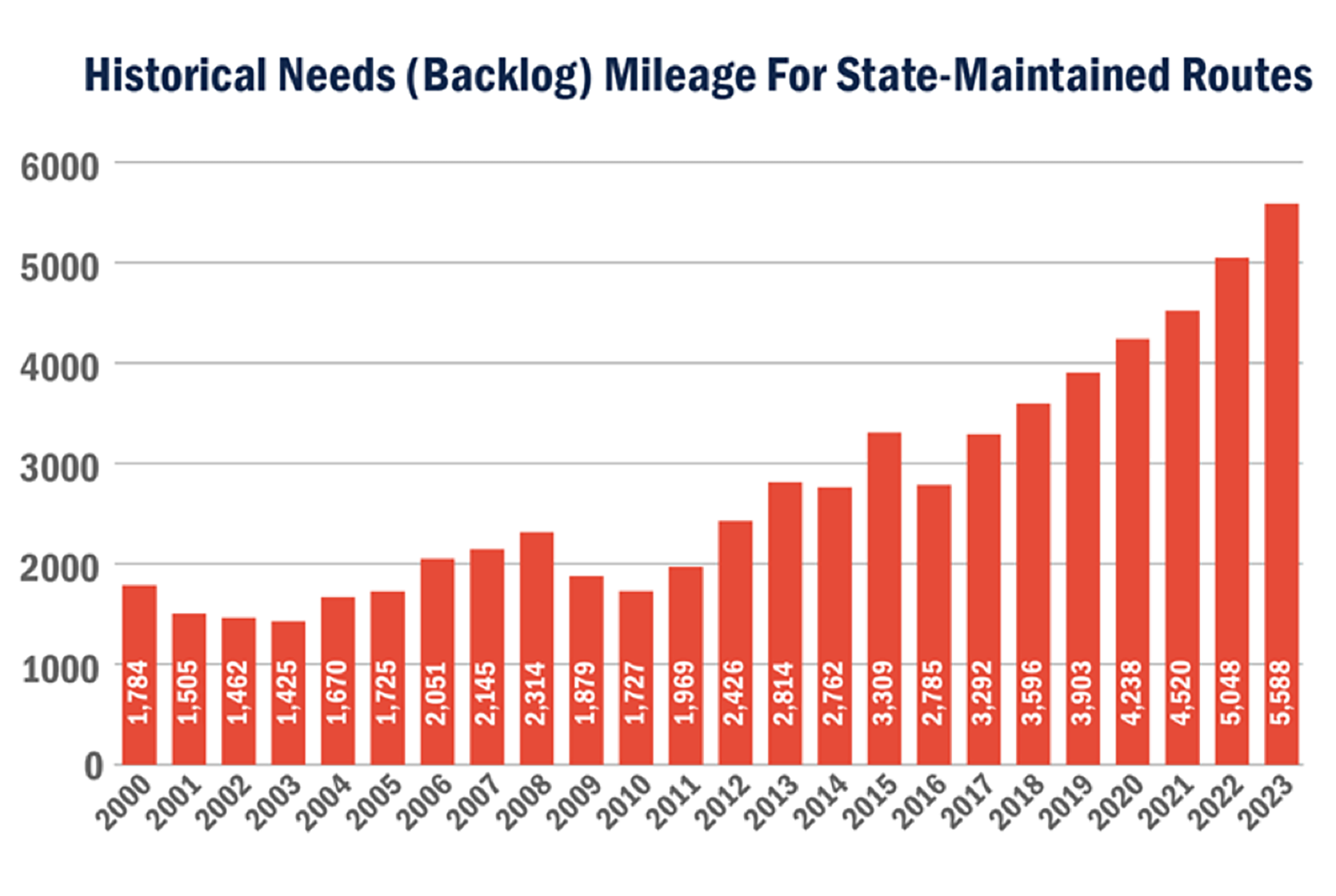

The most effective performance measures drive decisions that are important to the success of the program. For example, maintenance departments may use performance measures that track actual expenditures to planned expenditures to ensure that available funding is directed towards the highest-priority items, as shown in the North Carolina DOT practice example.

It is also important that the measures drive the desired performance within an organization. For instance, a performance requirement that measures whether pavement or bridge designs are submitted on time might cause incomplete or incorrect submittals to meet a deadline, leading to an increase in construction modifications. A more effective measure might focus on a minimal number of design modifications during the construction phase of a project.

Effective performance measures should also primarily be outcome-based rather than output-based, meaning that they focus on the result or impact of an activity rather than the inputs that went into the activity. Outcome-based measures are generally preferred because they indicate the effect on the traveling public resulting from the actions taken, so they usually relate to user priorities such as the length of time for a road to be cleared after a snow event or the absence of litter and graffiti. They are developed based on a description of what an agency wants to achieve as a result of the actions undertaken. Outcome-based measures are commonly used for managing ancillary assets such as drainage assets and signs. For instance, the performance of drainage assets might be reported in terms of the percent of pipes/culverts greater than 50 percent filled or otherwise deficient and the performance of signs might be reported in terms of the percent of signs viewable at night.

Output-based measures, on the other hand, track the resources used to achieve the outcome, such as the number of hours of labor used or the number of light-bulbs changed in a month. While the data is important information for managing resources, it does not necessarily drive outcomes that would matter to the public. For instance, travelers on a highway are much more interested in knowing when the road will be cleared of snow than how much overtime went into the operation.

When possible, agencies should use performance measures that are leading measures rather than lagging measures to influence future decisions. A leading measure uses changes in performance to provide insights into potential changes that might influence a future decision one way or another. For example, knowledge that a ramp meter has exceeded the manufacturer’s suggested service life might drive a decision to replace that meter. Similarly, increases in equipment downtime might indicate risks due to an aging fleet are growing or that planned operational activities will not be performed as planned. A lagging measure, on the other hand, looks back on the results of past investment strategies after the decisions have been made. Because a lagging measure is recorded after the fact, there is a delay (lag) in the agency’s ability to adjust its practices and improve performance. Bridge and pavement condition measures are examples of lagging measures because the reported conditions reflect the impact of decisions made several years in the past. Lagging measures are commonly used to evaluate a program’s effectiveness or to verify that actual investments achieved projected results.

In transportation, an agency might have a lagging measure for tracking complaints responded to within a 48-hour window. The measure provides an indication of the public’s satisfaction with the road network and is easy to monitor and report. However, if an agency really wants to effect change, it might develop leading measures to track the percent of complaints not worked on within a two-hour window or the percent of complaints that can’t be resolved by the initial point of contact and must be passed to someone else. Focusing on these types of measures could drive agency decisions to ensure complaints are being worked on quickly and are being assigned to the right people. General characteristics of effective performance measures are presented in Table 6.1.

TIP

Outcome-based measures better relate to performance characteristics noticed by the public and other stakeholders than output-based measures.

Ancillary Asset Management

Table 6.1 - Desired Performance Measure Characteristics

| Desired Characteristics | Rationale/Purpose |

|---|---|

| Measurable with available tools/data | May require no additional cost for data collection |

| Forecastable | Enables data-driven target setting based on future conditions |

| Clear to the public and lawmakers | Allows performance story-telling to customers and policymakers |

| Agency has influence over result | Measures agency activities rather than impact of external factors |

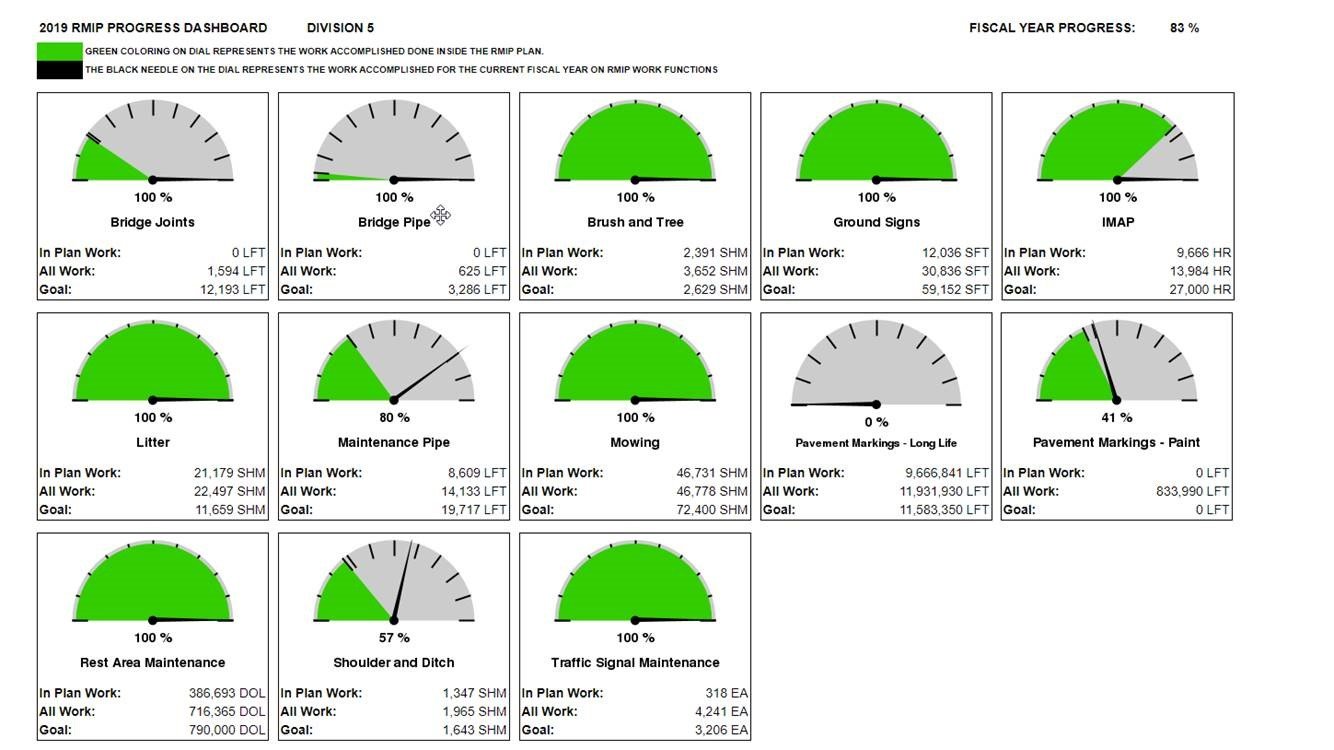

North Carolina DOT

The North Carolina DOT authorizes its divisions to determine how funding will be used for maintenance activities and uses performance data to assist with this activity. Each year, Division Engineers submit annual plans detailing what work will be accomplished; these plans are reviewed quarterly with the Chief Engineer to discuss actual versus planned work. Their accomplishments are also displayed in a dashboard for internal use, as shown in the following image. Public-facing dashboards are also available showing overall conditions and performance trends. The Division Engineers are also held accountable for their performance, since their planned and actual performance data are incorporated into their annual evaluations.

Source: Leading Management Practices in Determining Funding Levels for Maintenance and Preservation. Scan Team Report, NCHRP Project 20-68A, Scan 14-01, National Cooperative Highway Research Program, May 2016.

Use of Performance Measures

Performance measures are used to:

- Connect agency policies and objectives to investment decisions.

- Establish desired and targeted levels of service that consider past performance, current and future demand, stakeholder priorities, and anticipated funding.

- Align agency policies, investments, and day-to-day practices in a meaningful and easily understood manner.

- Prioritize investment needs.

- Monitor and report progress towards desired objectives to both internal and external stakeholders in a consistent, cost-effective, and transparent manner as illustrated in practice examples from the Washington State, North Carolina, and Virginia DOTs.

Washington DOT

The Washington DOT uses its Maintenance Accountability Process (MAP) to comprehensively manage maintenance budgets and to communicate the impacts of policy and budget to both internal and external stakeholders. Field condition surveys are conducted annually to assess the condition of 14 assets on the highway system such as signs and signals, ITS assets, tunnels, and highway lighting. For each asset, a level of service target is established, based on expected funding levels and importance of the asset to the agency’s strategic objectives. The targeted and actual performance is summarized on a statewide basis and presented to the legislature, media, internal stakeholders, and other DOTs in a format similar to what is shown in the figure (https://www.wsdot.wa.gov/NR/rdonlyres/8EC689DF-9894-43A8-AA0F-92F49AC374F5/0/MAPservicelevelreport.pdf). In 2018, Washington State DOT achieved 77 percent of its highway maintenance targets. Targets that were not achieved are shown as red bullseyes and areas where the targets were exceeded include a checkmark with the bullseye. The results illustrate where additional investment is needed on a statewide basis and provides a basis for setting maintenance priorities during the year.

Targeted and Actual Performance Results Used to Set Maintenance Priorities

Source: WSDOT. 2017. Multimodal Asset Performance Report. Washington State DOT. https://wsdot.wa.gov/publications/fulltext/graynotebook/Multimodal/AssetPerformanceReport_2017.pdf

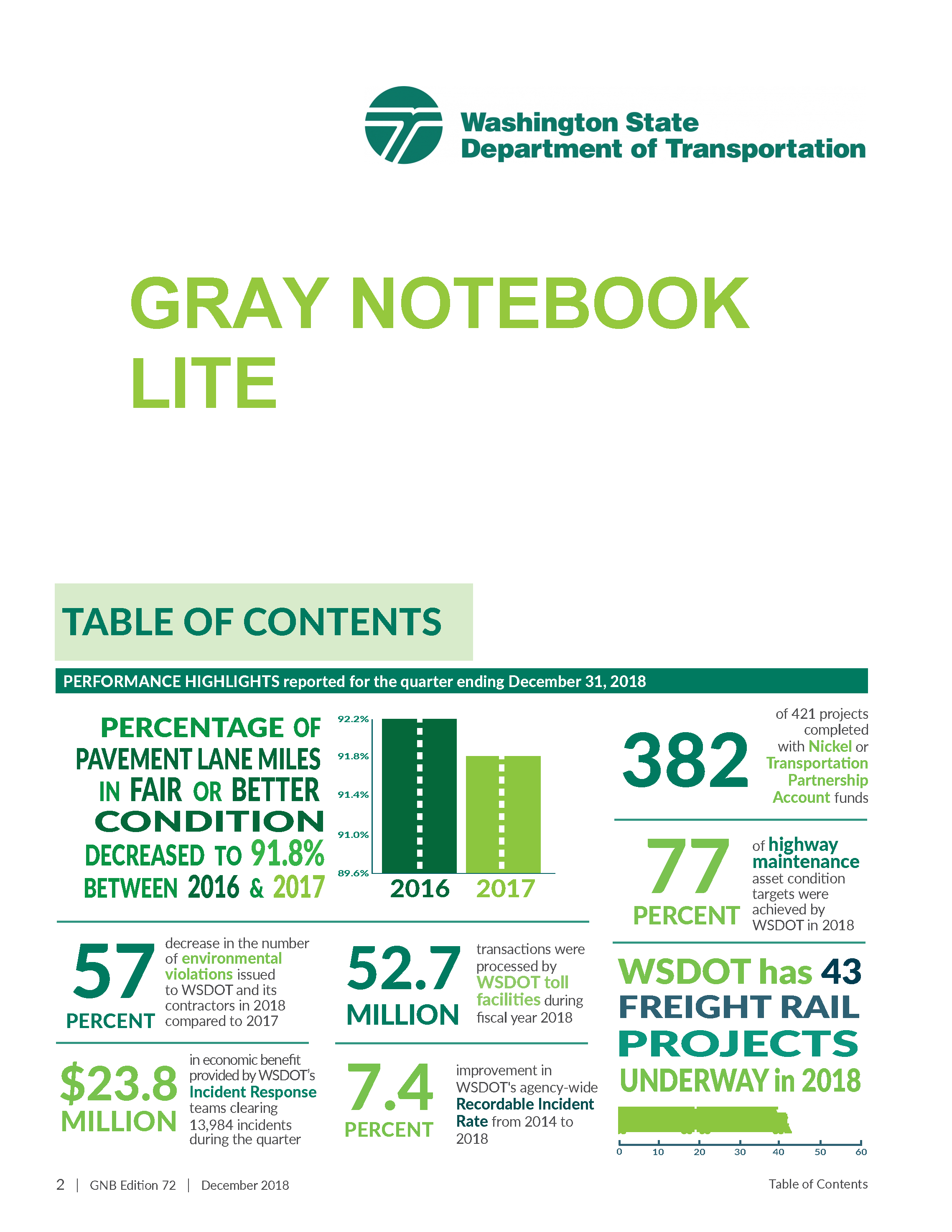

Washington DOT

To support accountability, credibility, and transparency, the Washington State DOT publishes its quarterly performance report, referred to as The Gray Notebook. Each edition of the Gray Notebook presents updates on multimodal systems' and programs' key functions and analysis of performance in strategic goal areas based on information reported to the Performance Management and Strategic Management offices of the Transportation Safety and Systems Analysis Division. Washington State DOT also publishes its Gray Notebook Lite, which highlights key metrics referenced in the Gray Notebook in a format for quick reading. Examples from each of these documents are presented in the figures.

The Gray Notebook and the Gray Notebook Lite

Source: WSDOT. 2019. https://wsdot.wa.gov/about/accountability/gray-notebook

Virginia DOT

Performance dashboards are also a popular way to present progress, using color-coded indicators similar to those on the dash of an automobile. An example of the interactive dashboard available from the Virginia DOT is shown in the figure. The screen reports performance in seven areas (performance, safety, condition, finance, management, projects, and citizen survey results) and the needles indicate whether the performance is within targeted ranges. Hyperlinks are available in each area if a user wants to explore historical trends or explore performance objectives in more detail.

Virginia DOT's Performance Dashboard

Source: Virginia DOT. 2019. http://dashboard.virginiadot.org/

Future Directions in Performance Measures

As agencies advance the maturity of their practices and move towards investment decisions across assets and modes (as discussed in Chapter 5), there is increasing interest in the use of leading measures and asset performance measures that can be used in concert with asset condition measures.

Asset management plans document the processes and investment strategies developed by an agency to manage its infrastructure assets. These asset management plans support an agency’s performance-based planning and programming processes for making long-term investment decisions and feed shorter-term project and treatment selection activities. Together, these activities ensure the investment decisions of an agency are aligned with performance objectives and goals.

Examples of innovative new performance measures include:

- Financial Measures – Internationally, financial performance measures have been used successfully to express whether the level of investment has been adequate to offset the rate of asset deterioration or depreciation. For example, the Queensland Department of Infrastructure and Planning uses an Asset Sustainability Ratio defined as the capital expenditure being made on asset renewals (e.g., improvements) divided by the depreciation expense (discussed further in Chapter 4). If the ratio is less than 100 percent, the level of investment is not adequately replacing the depreciation occurring each year. Queensland also uses an Asset Consumption Ratio comparing the current value of the depreciable assets to their replacement value in order to show the aged condition of the assets.

In the United States, some agencies are evaluating the use of an Asset Sustainability Index (ASI), which is the ratio of the budget allocated to address needed improvements identified by a pavement or bridge management system (FHWA. 2012. Asset Sustainability Index: A Proposed Measure for Long-Term Performance, Federal Highway Administration, Washington, D.C.). The ASI is a unitless measure that allows comparisons across asset classes and provides an overall assessment of the adequacy of an agency’s investment in its assets. Since it is unitless, an agency could individually calculate a Maintenance Sustainability Ratio, a Pavement Sustainability Ratio, and a Bridge Sustainability Ratio that are all combined into an overall ASI. One of the difficulties in calculating the ASI is defining the needed level of investment since needs are significantly impacted by targeted condition levels. Slight changes in targeted conditions can have a significant impact on the resulting ASI calculation.

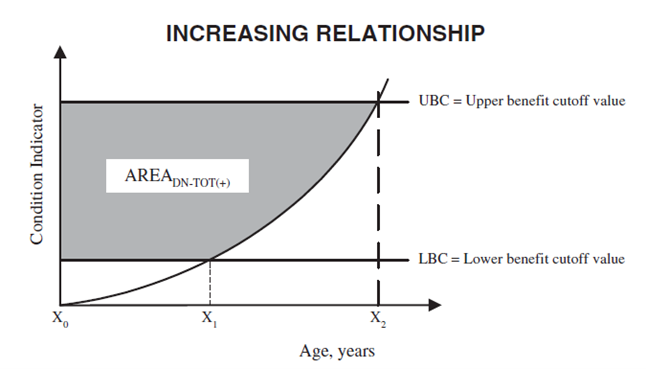

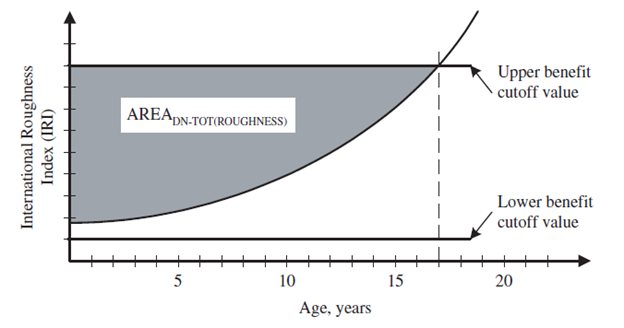

- Life Cycle Measures - A life cycle performance measure is a relatively new leading measure, promoting the selection of sound, long-term strategies best able to maximize performance at the lowest possible cost. There are several life cycle performance measures under consideration, including the Remaining Service Interval (RSI), validated under an FHWA-sponsored research project. The RSI is based on identifying a structured sequence of the type and timing of various repair and replacement actions needed to achieve a desired LOS over a long timeframe at the minimum practicable cost. The results of the RSI evaluation may be used to generate a Life Cycle Impact Factor, summarizing the difference in life cycle costs associated with the various strategies being considered. Documentation from a pilot implementation of the RSI approach is available through the FHWA (https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/research/infrastructure/pavements/21006/21006.pdf).

- Sustainability Measures – With an increased focus on identifying long-term sustainable solutions to transportation system needs, agencies may seek to develop new sustainability performance measures in order to properly indicate the impact a proposed solution may have on environmental conditions. The use of a recycling measure for gauging the amount of recycled material used in road construction is an example of this type of measure, as are measures for monitoring carbon dioxide emissions.

- Equity Measures -The increased emphasis on equity, inclusion, and diversity is impacting planning and investment decisions at several transportation agencies. As equity considerations are added, there has been some discussion related to the types of measurable performance measures that can be used without bias toward certain users or modes of transportation. In a case study prepared by the FHWA’s Transportation Asset Management Expert Task Group, a suggestion was made to further explore both quantitative and qualitative performance measures in this area.

TIP

Making performance measures publicly available through reports, scorecards, or dashboards increases transparency into agency operations, which can serve as motivation to improve staff’s desire to meet the standards established, thereby increasing the chance of success.

North Carolina DOT

The North Carolina DOT has an interactive Organizational Performance Scorecard that provides an online indicator of the Department’s success at meeting targets in the following six core goal areas:

- Make Transportation Safer.

- Provide Great Customer Service.

- Deliver and Maintain Infrastructure Effectively and Efficiently.

- Improve Reliability and Connectivity of Transportation Systems.

- Promote Economic Growth Through Better Use of Infrastructure.

- Make NCDOT a Great Place to Work.

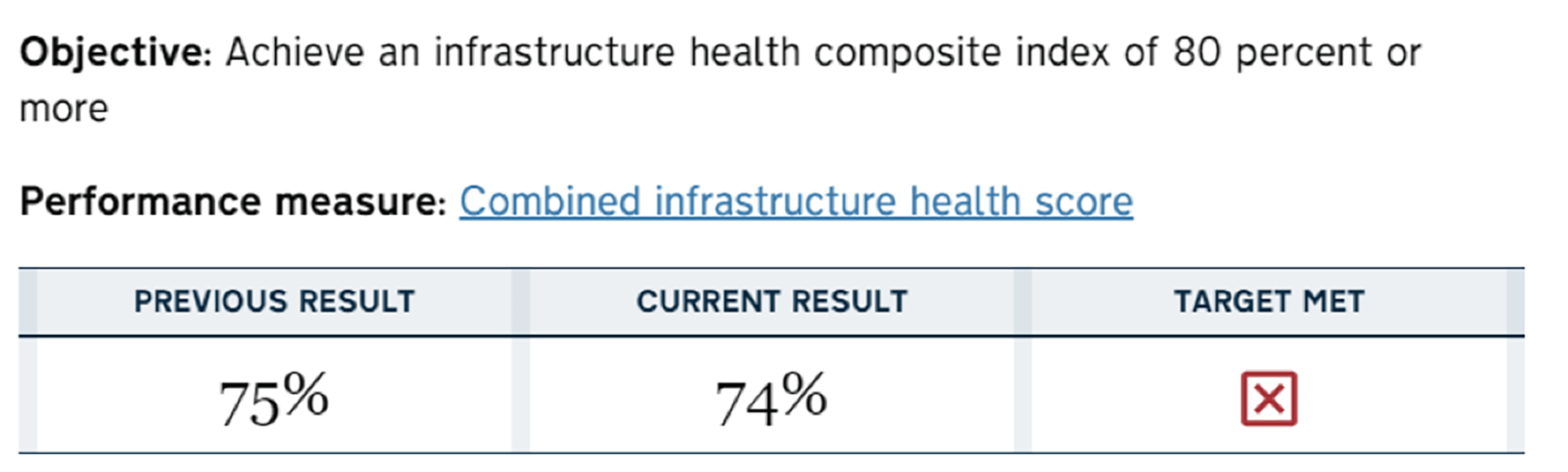

An example of how the information is shown; it presents the target for an overall infrastructure health index and the most recent results. As shown by the red “x” in the box on the far right, NCDOT is not currently meeting its target of a health index of 80 percent or more.

North Carolina DOT’s Organizational Performance Scorecard Website – Excerpt

Source: NCDOT. 2019.https://www.ncdot.gov/about-us/our-mission/Performance/Pages/default.aspx

Evaluating the Effectiveness of Performance Measures 6.1.2

Because of the important role performance measures have in supporting performance-based decisions, agencies should use care in selecting measures that drive the right types of results. This section introduces several approaches to evaluate the effectiveness of an agency’s performance measures.

Assessment

TPM Webinar #17 - Agency Innovations and Improvements Blitz

In its handbook for agency executives, AASHTO suggests an assessment of performance measures should consider the following:

- Is the number of performance numbers reasonable? – An agency should retain performance measures addressing critical areas of importance that are maintainable with time. The Maryland and New Mexico DOTs have approximately 80 measures reviewed on a regular basis, but the Florida and Pennsylvania DOTs use approximately 15 to 20 measures to review strategic performance. Some agencies identify a small number (< 10) of KPIs selected from the pool of operational and tactical measures that best reflect an agency’s progress toward achieving its overall goals.

- Are the measures meaningful? – Some agencies choose only to use easily measured performance activities because the information is easy to obtain. However, other measures may do a better job of driving good decision making.

- Does the level of detail in data collection match the level of detail required to drive decisions? – Agencies should balance data availability with the analytic rigor used to make decisions. For instance, if pavement markings are replaced every year, it is not necessary to collect retro-reflectivity information annually. Similarly, collecting data on one lane of a two-lane highway may be enough for approximating the condition across the full width of the roadway.

- Do they support the right decisions? – The performance measures should drive decisions in support of strategic objectives. For example, a performance measure based on the amount of overtime incurred after a snow event is less effective than one able to monitor the number of hours until the roads are cleared.

- Are existing data sources reliable? – In most situations, existing data can provide the information needed for performance management, but it must be reliable and maintained regularly to be useful.

An assessment of performance measures can be important, since many organizations find that over time, the number of performance measures they are managing can become unwieldy.

Pennsylvania DOT

After using performance measures for years, the Pennsylvania DOT recognized that the number of measures being used had increased to a level that was difficult to manage. In 2011, the Pennsylvania DOT conducted an assessment of their performance measures using the following series of questions to guide their decisions as to which measures to keep, which to change, or which to delete:

- Who is using the measure?

- What exactly is being measured?

- Why is this particular measure needed?

- Whose performance is being measured?

- Is the performance goal defined?

- Does a similar measure already exist?

- Is the existing measure meeting the needs and intent or should it be modified?

If a measure was needed where no measure exists, the following additional questions were used:

- Does the measure affect continuous improvement?

- Is the data for the measure updated as frequently as needed? Should it be updated monthly, quarterly, or yearly?

- Is the measure easy to quantify?

- Is the measure easy to understand?

- Is it clear who owns the measure?

- Does the measure provide a means of comparison?

- Have unintended consequences been investigated?

- Can the unintended consequences be successfully mitigated?

The process has helped to ensure that the agency is focused on the right measures to drive desired results and behaviors. The analysis found several issues that could be addressed, including eliminating duplicate or overly complicated measures, modifying measures that were driving unintended consequences, and resolving data quality issues.

SMART Evaluation

As discussed earlier, performance measures are used to set desired or targeted levels of service. Targets may be short-term, such as the 2- and 4-year targets state DOTs are required to submit to FHWA, or they may be long-term targets, such as the desired State of Good Repair (SOGR) serving as the basis for an agency’s TAMP.

Performance targets are evaluated using the “SMART” method, which evaluates whether targets are:

- Specific. The performance is explicitly described.

- Measurable. Progress towards the target can be monitored in a consistent manner.

- Achievable. The target considers past performance, expected changes in demand, available resources and other considerations that make it realistic.

- Relevant (also referenced as results-oriented). The target should be meaningful to the agency and drive the right outcomes.

- Time-related (also referenced as timely or time-bound). There is a stated timeframe for achieving the target.

Nevada DOT

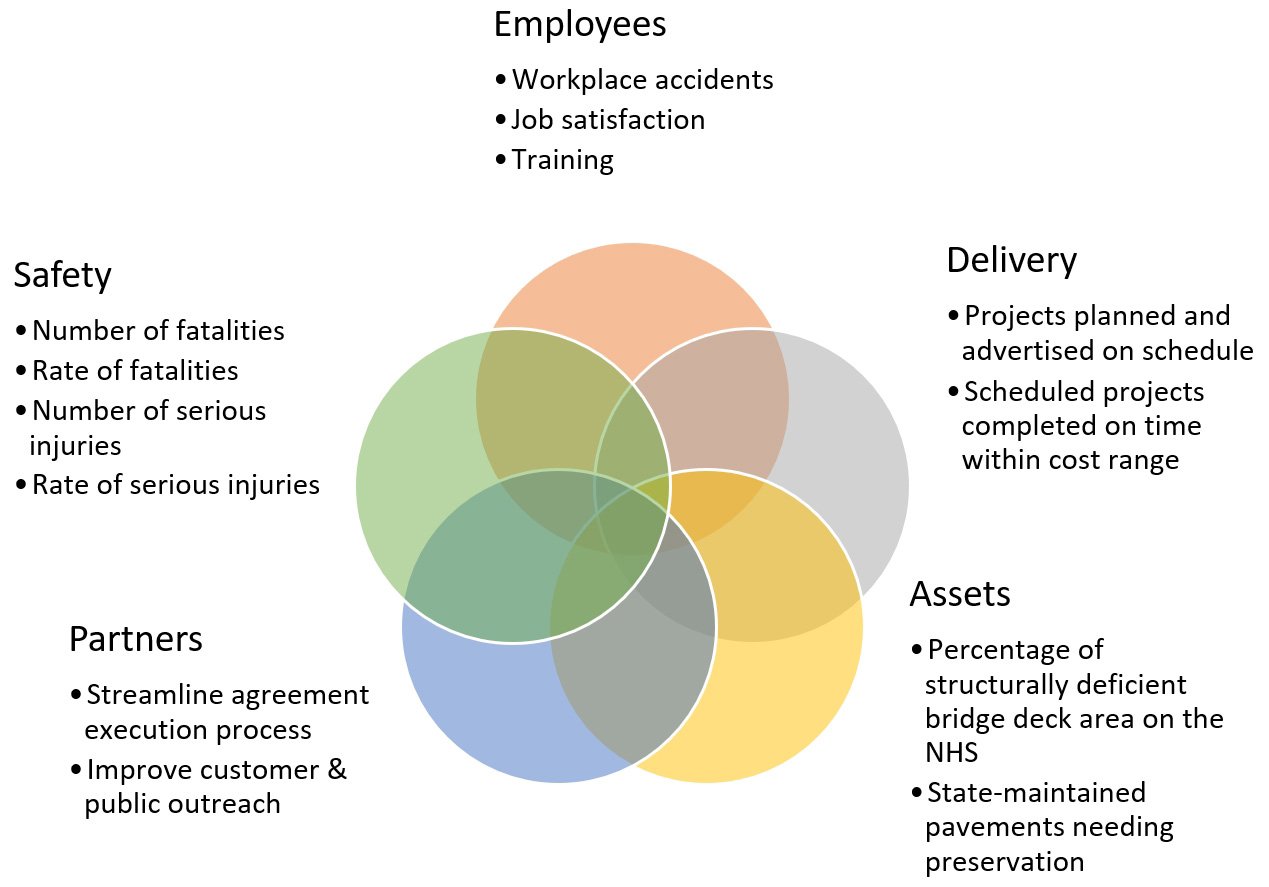

The Nevada DOT recognized that although performance measures were being reported regularly, they were not driving agency policies or decisions. The assessment evaluated the performance measures being used in each of the five key performance areas shown in the figure as well as the organizational culture to support performance management.

The study recommended improvements to emphasize the importance of messaging in order to advance the agency’s performance management culture, extend the performance culture beyond the headquarters office to field staff, and develop job performance plans emphasizing accountability at the division, office and unit levels. The study also recommended the periodic review of performance measures to ensure their continued relevance to agency business processes.

Nevada DOT’s five key performance areas and measures

Source: Nevada DOT. 2017. Adapting a Culture for Performance Management at the Nevada Department of Transportation.

Benchmarking