- Chapters

-

Chapter 6

Sections - Chapter 6 Home Page

- Chapter PDF

Chapter 6

Quick Links

6.6.2

Capturing Maintenance Cost and Accomplishment Data

This subsection discusses the challenges of capturing maintenance costs for TAMPs, particularly when maintenance work is delivered by in-house crews or through different contract mechanisms. It emphasizes the need to align costs from different sources, such as in-house and contract maintenance costs, both financially and in terms of units of accomplishment. Examples are provided to illustrate approaches for aligning and tracking maintenance costs.

Introduction

The majority of asset management costs, for large transportation agencies, are contract costs for preservation, renewal, and construction of assets. However, maintenance investments have a significant impact on asset conditions and should be accounted for in a TAMP. Capturing maintenance costs for inclusion in a TAMP often poses unique challenges, because maintenance work is often delivered by in-house crews or through different contract mechanisms than major capital projects. These costs may also be tracked through different IT systems than capital costs.

When capturing costs for incorporation into a TAMP, it is also important to capture what is purchased, or accomplished, with those investments. Maintenance accomplishments are typically captured in terms of maintenance activities. However, the units of accomplishment for these activities may not easily align with asset management measures. Further the units of accomplishment may vary between work performed by in-house crews and work performed by contract.

In-House Maintenance Costs

Maintenance crews commonly report their efforts and accomplishments on a daily basis through a work reporting system. Most State DOTs currently use some form of maintenance management systems (MMS) to report work performed, along with the resulting accomplishments and costs.

In-house maintenance costs commonly include the cost of labor, equipment, materials, and overhead expenses related to work performed by maintenance field crews. These costs are captured through work order or daily report records, in which costs are associated with one or more actions, commonly called “tasks,” performed by the crew. Each task has an associated task code, which serves as a unique identifier, and a specific unit of measure for reporting accomplishments. For example, the task of “ditch cleaning” may have a unit of accomplishment of “feet,” or the task of “mowing” may have a unit of accomplishment of “acres.”

Contract Costs

Maintenance contract costs, like typical construction contract costs, are captured in terms of contract pay items. These pay items commonly do not align with the maintenance. Moreover, the unit of accomplishment may depend on the type of contract used to procure the work. For example, a contract to clean ditches may have a pay item measured in feet of ditch cleaned, cubic yards of material removed, or hours of work performed.

Maintenance contracts may be funded from an agency's Capital program or Maintenance budget. In many cases maintenance contracts funded through different programs are managed with different systems and have different means of tracking both costs and accomplishments. All of these differences can make tracking maintenance costs more challenging than the costs for other work types.

Aligning Costs from Different Sources

To incorporate maintenance costs into a TAMP, the costs from multiple sources need to be aligned in regard to both their financial components and their units of accomplishment.

The primary source of misalignment between in-house and contract maintenance costs is that in-house costs are captured through individual components of labor, equipment, materials, and overhead, whereas contract costs are captured based on pay items that combine each of these components. The labor costs captured through maintenance management systems (MMS) may or may not include an estimate of overhead costs. To facilitate comparison of in-house labor costs to contract costs an overhead multiplier should be applied. Best practices for ensuring in-house costs are accurate includes interfacing the maintenance management systems with the agency’s financial or enterprise resource planning (ERP) system.

Once the costs are aligned financially, they must be aligned to common units of accomplishment to allow them to be incorporated into asset management analyses. The Maryland DOT State Highway Administration (MDOTSHA) and Texas DOT (TxDOT) offer two examples of how this alignment can be accomplished. These examples are taken from NCHRP Report 1076, Guide for Incorporating Maintenance Costs into a Transportation Asset Management Plan. TxDOT’s approach requires inspectors on maintenance contracts to enter daily accomplishment information into both the Capital Program management system, SiteManager, and the MMS. MDOTSHA has developed a set of Project Cost Activity (PCA) codes to track in-house maintenance expenses. These codes are incorporated into the records of all maintenance contracts to facilitate alignment of costs and accomplishments.

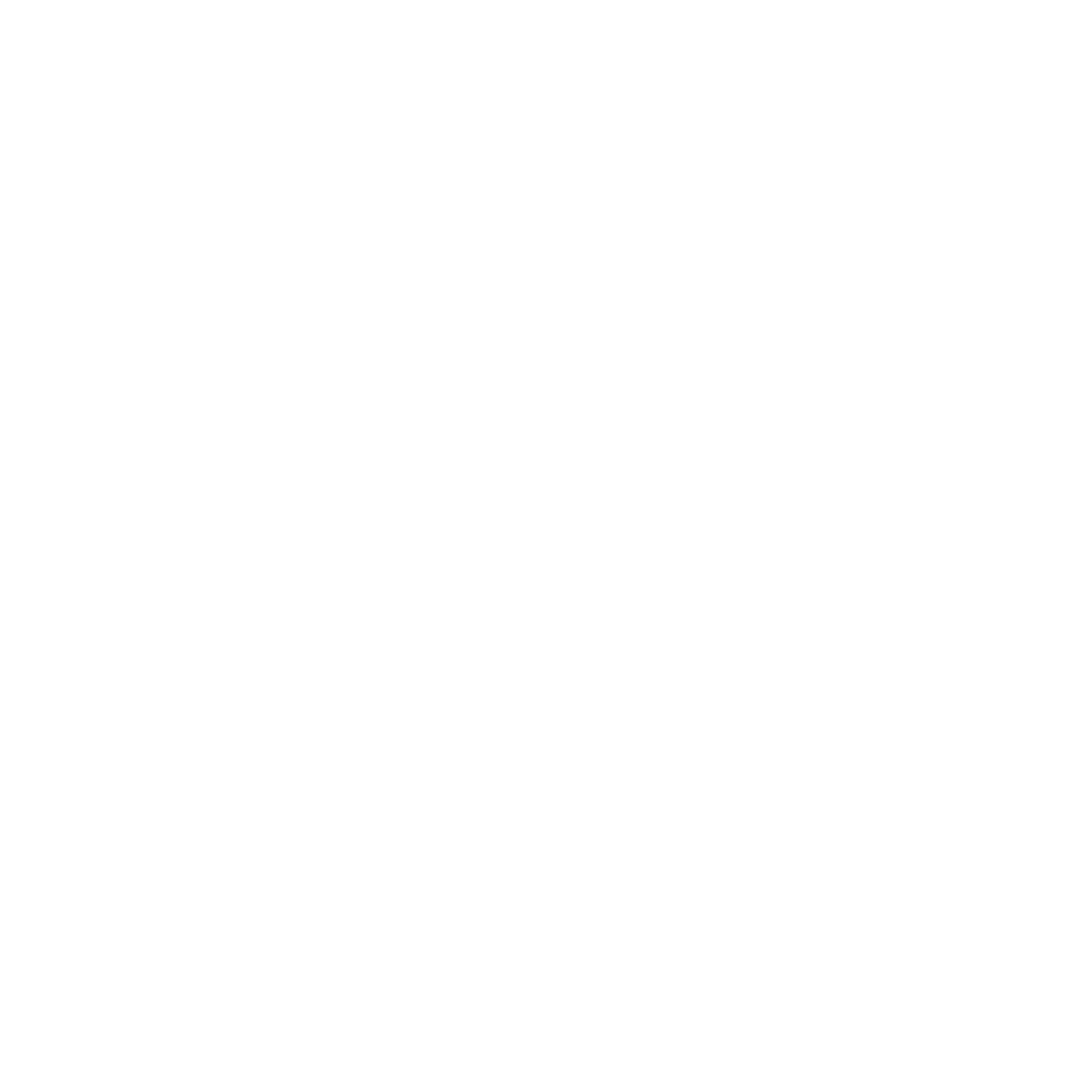

Maryland DOT

The MDOT SHA reports labor, equipment, and materials costs for its State forces’ work into the electronic team activity cards (eTAC) system. These costs are captured by asset or unit. MDOT SHA enters contract data into the FHWA Financial Management Information System (FMIS) and other contract management software. The contract systems and eTAC assign a Project Cost Activity (PCA) code for each expense. The PCA codes allow the costs from similar work, delivered by different means, to be aggregated. The PCA codes are linked to the twenty-one Maryland Condition Assessment Reporting System (MCARS) elements to align costs with asset performance. MDOT SHA uses QlikView to aggregate the work output, cost data, and MCARS data and associate each to the appropriate PCA code for the work activity accomplished (see Figure 6-B, a screenshot of QlikView provided by MDOT SHA). Data aggregation with QlikView works well if data is accurate with the PCA codes, costs, and accomplishments.

Screenshot of QlikView

Source: MDOT SHA

This approach enables MDOT SHA to perform an analysis to determine whether in-house or contracted maintenance provides a more cost-efficient result for the activity or asset. This is an important analysis to consider when developing maintenance work programs as it allows an agency to be strategic with limited resources” (Allen, et. al. 2023).

*Note: This practice example was derived from NCHRP Research Report 1076: A Guide to Incorporating Maintenance Costs into a Transportation Asset Management Plan.

Texas DOT

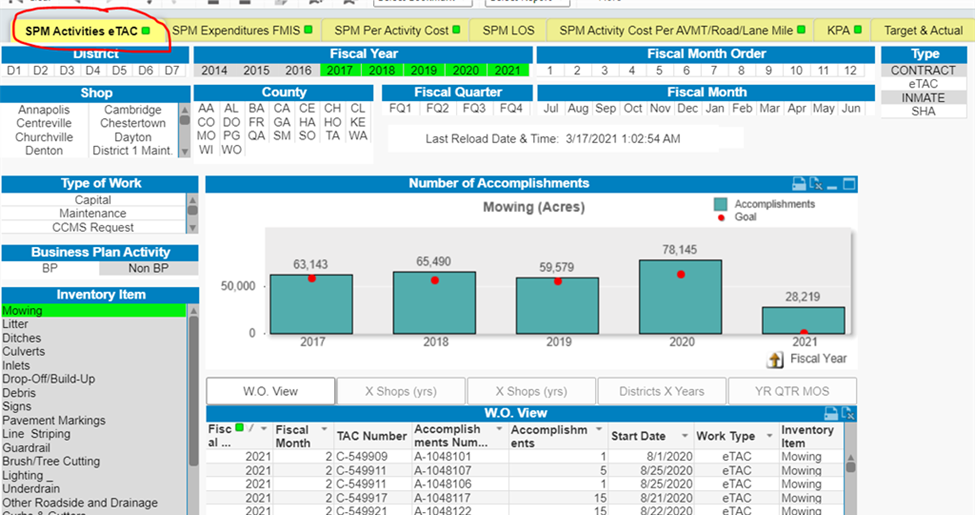

TxDOT provides an example of effective contract maintenance cost data collection processes. TxDOT contracts approximately 52 percent ($620 million) of its $1.2 billion maintenance budget for routine maintenance. Contracted work is interfaced into TxDOT’s MMS in two ways: from its enterprise resource planning (ERP) software and from its construction contract management software. TxDOT typically uses work orders (WO) for contracts less than $25,000. The process for capturing and reporting contract maintenance costs is shown in Figure 6-A.

Figure 6-A: TxDOT Contract Purchase Order Data Collection Process

Source: Texas DOT

For larger projects, TxDOT utilizes AASHTOWare Site Manager, including the Routine Maintenance Contract Administration module. Daily work reports allow inspectors to capture work performed at the job site such as personnel, equipment, work items, quantities, descriptions, etc. Over 3,700 pay items are used on routine maintenance contracts and the Maintenance Distribution Window, a custom upgrade to Site Manager, ties the pay item cost to the MMS function code (i.e., what work is being performed) and amount of work performed. The MMS then provides reports by function code for both in-house and contracted work and TxDOT actively monitors data quality to ensure accurate reporting and analysis” (Allen, et. al. 2023).

*Note: This practice example was derived from NCHRP Research Report 1076: A Guide to Incorporating Maintenance Costs into a Transportation Asset Management Plan.