- Chapters

-

Chapter 6

Sections - Chapter 6 Home Page

- Chapter PDF

Chapter 6

Quick Links

Section 6.6 NEW SECTION

Incorporating Maintenance Costs into a TAMP

As discussed in section 6.4 monitoring asset work and costs is essential to assessing progress towards TAM objectives and continually improving TAM analyses and forecasts. This section describes specific challenges and approaches to capturing costs related to the maintenance of highway infrastructure assets.

Incorporating Maintenance Costs into a TAMP

As discussed in section 6.4 monitoring asset work and costs is essential to assessing progress towards TAM objectives and continually improving TAM analyses and forecasts. This section describes specific challenges and approaches to capturing costs related to the maintenance of highway infrastructure assets.

- Chapters

-

Chapter 6

Sections - Chapter 6 Home Page

- Chapter PDF

Chapter 6

Quick Links

6.6.1

Categorizing and Tracking Maintenance Activities and Costs

Maintenance can be performed at any stage of the asset life cycle. Some maintenance work may or may not change the measured asset condition, extend the expected asset life cycle, or reduce risk. NCHRP Report 1076: Guide for Incorporating Maintenance Costs Into a TAMP establishes five categories of maintenance work to be considered in the incorporation of maintenance costs into TAM Analyses.

Operations and Routine Maintenance

TAM Webinar #59 - Incorporating Maintenance Costs Into a TAMP

Operational and routine maintenance activities may restore or sustain the functionality of an asset, but they do not change measured asset conditions (e.g., road patrol, mowing, and snow and ice control). These activities do not typically have a direct impact on an asset’s service life. Therefore, these are activities that are not generally considered in lifecycle planning (LCP) analysis. An absence of routine maintenance may increase the likelihood of some risks, as the performance of these tasks is typically assumed as part of the highway design process (Allen, et. al. 2023).

Preventive Maintenance

As the name indicates, preventive maintenance prevents or addresses deterioration to delay a decline in measured conditions but does not significantly improve conditions. Common examples include crack seal, chip seal, sweeping, drain cleaning, bridge washing (Allen, et. al. 2023).

Repair

Repairing damage or deterioration improves the measurable asset condition and restores function but does not restore or improve structure, capacity, or functionality. Examples of repairs include milling and inlaying pavement, bridge deck repairs, and bridge member repairs. These activities may include replacement of parts but not major components. The quantity of repair, rather than the type of activity, is what typically designates an activity as maintenance instead of rehabilitation or preservation (Allen, et. al. 2023).

Unit or Major Component Repair

Unit or component replacement goes beyond repair to remove and replace one or more individual asset components, restoring functionality for that component. Examples include sign panel replacement, striping, and traffic signal component replacement. For some assets, such as ground mounted signs, the entire asset may be replaced under a maintenance action because of the mechanism by which the replacement is delivered or funded (Allen, et. al. 2023).

Organizational Strengthening

Organizational strengthening includes activities that are not directly asset related. These activities may mitigate risk or improve organizational capacity. Examples include training, emergency preparedness, management systems and their use (Allen, et. al. 2023).

- Chapters

-

Chapter 6

Sections - Chapter 6 Home Page

- Chapter PDF

Chapter 6

Quick Links

6.6.2

Capturing Maintenance Cost and Accomplishment Data

This subsection discusses the challenges of capturing maintenance costs for TAMPs, particularly when maintenance work is delivered by in-house crews or through different contract mechanisms. It emphasizes the need to align costs from different sources, such as in-house and contract maintenance costs, both financially and in terms of units of accomplishment. Examples are provided to illustrate approaches for aligning and tracking maintenance costs.

Introduction

The majority of asset management costs, for large transportation agencies, are contract costs for preservation, renewal, and construction of assets. However, maintenance investments have a significant impact on asset conditions and should be accounted for in a TAMP. Capturing maintenance costs for inclusion in a TAMP often poses unique challenges, because maintenance work is often delivered by in-house crews or through different contract mechanisms than major capital projects. These costs may also be tracked through different IT systems than capital costs.

When capturing costs for incorporation into a TAMP, it is also important to capture what is purchased, or accomplished, with those investments. Maintenance accomplishments are typically captured in terms of maintenance activities. However, the units of accomplishment for these activities may not easily align with asset management measures. Further the units of accomplishment may vary between work performed by in-house crews and work performed by contract.

In-House Maintenance Costs

Maintenance crews commonly report their efforts and accomplishments on a daily basis through a work reporting system. Most State DOTs currently use some form of maintenance management systems (MMS) to report work performed, along with the resulting accomplishments and costs.

In-house maintenance costs commonly include the cost of labor, equipment, materials, and overhead expenses related to work performed by maintenance field crews. These costs are captured through work order or daily report records, in which costs are associated with one or more actions, commonly called “tasks,” performed by the crew. Each task has an associated task code, which serves as a unique identifier, and a specific unit of measure for reporting accomplishments. For example, the task of “ditch cleaning” may have a unit of accomplishment of “feet,” or the task of “mowing” may have a unit of accomplishment of “acres.”

Contract Costs

Maintenance contract costs, like typical construction contract costs, are captured in terms of contract pay items. These pay items commonly do not align with the maintenance. Moreover, the unit of accomplishment may depend on the type of contract used to procure the work. For example, a contract to clean ditches may have a pay item measured in feet of ditch cleaned, cubic yards of material removed, or hours of work performed.

Maintenance contracts may be funded from an agency's Capital program or Maintenance budget. In many cases maintenance contracts funded through different programs are managed with different systems and have different means of tracking both costs and accomplishments. All of these differences can make tracking maintenance costs more challenging than the costs for other work types.

Aligning Costs from Different Sources

To incorporate maintenance costs into a TAMP, the costs from multiple sources need to be aligned in regard to both their financial components and their units of accomplishment.

The primary source of misalignment between in-house and contract maintenance costs is that in-house costs are captured through individual components of labor, equipment, materials, and overhead, whereas contract costs are captured based on pay items that combine each of these components. The labor costs captured through maintenance management systems (MMS) may or may not include an estimate of overhead costs. To facilitate comparison of in-house labor costs to contract costs an overhead multiplier should be applied. Best practices for ensuring in-house costs are accurate includes interfacing the maintenance management systems with the agency’s financial or enterprise resource planning (ERP) system.

Once the costs are aligned financially, they must be aligned to common units of accomplishment to allow them to be incorporated into asset management analyses. The Maryland DOT State Highway Administration (MDOTSHA) and Texas DOT (TxDOT) offer two examples of how this alignment can be accomplished. These examples are taken from NCHRP Report 1076, Guide for Incorporating Maintenance Costs into a Transportation Asset Management Plan. TxDOT’s approach requires inspectors on maintenance contracts to enter daily accomplishment information into both the Capital Program management system, SiteManager, and the MMS. MDOTSHA has developed a set of Project Cost Activity (PCA) codes to track in-house maintenance expenses. These codes are incorporated into the records of all maintenance contracts to facilitate alignment of costs and accomplishments.

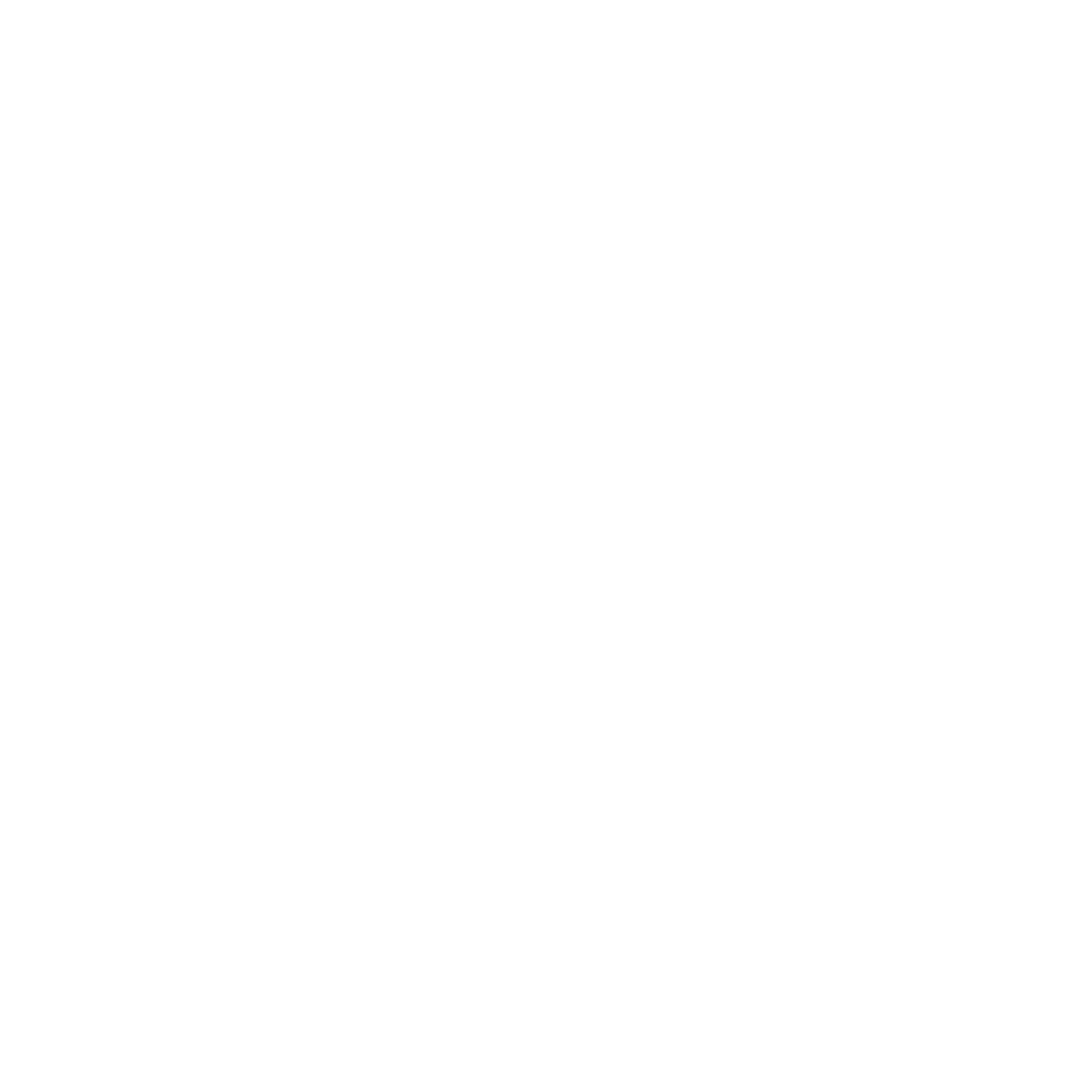

Maryland DOT

The MDOT SHA reports labor, equipment, and materials costs for its State forces’ work into the electronic team activity cards (eTAC) system. These costs are captured by asset or unit. MDOT SHA enters contract data into the FHWA Financial Management Information System (FMIS) and other contract management software. The contract systems and eTAC assign a Project Cost Activity (PCA) code for each expense. The PCA codes allow the costs from similar work, delivered by different means, to be aggregated. The PCA codes are linked to the twenty-one Maryland Condition Assessment Reporting System (MCARS) elements to align costs with asset performance. MDOT SHA uses QlikView to aggregate the work output, cost data, and MCARS data and associate each to the appropriate PCA code for the work activity accomplished (see Figure 6-B, a screenshot of QlikView provided by MDOT SHA). Data aggregation with QlikView works well if data is accurate with the PCA codes, costs, and accomplishments.

Screenshot of QlikView

Source: MDOT SHA

This approach enables MDOT SHA to perform an analysis to determine whether in-house or contracted maintenance provides a more cost-efficient result for the activity or asset. This is an important analysis to consider when developing maintenance work programs as it allows an agency to be strategic with limited resources” (Allen, et. al. 2023).

*Note: This practice example was derived from NCHRP Research Report 1076: A Guide to Incorporating Maintenance Costs into a Transportation Asset Management Plan.

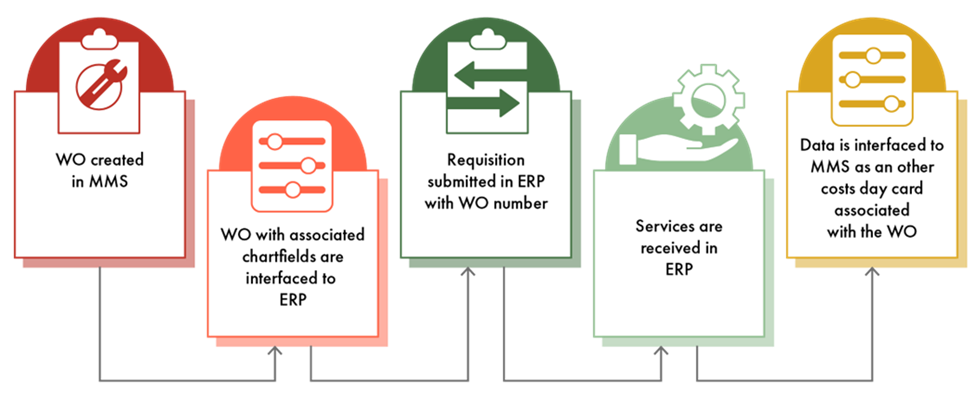

Texas DOT

TxDOT provides an example of effective contract maintenance cost data collection processes. TxDOT contracts approximately 52 percent ($620 million) of its $1.2 billion maintenance budget for routine maintenance. Contracted work is interfaced into TxDOT’s MMS in two ways: from its enterprise resource planning (ERP) software and from its construction contract management software. TxDOT typically uses work orders (WO) for contracts less than $25,000. The process for capturing and reporting contract maintenance costs is shown in Figure 6-A.

Figure 6-A: TxDOT Contract Purchase Order Data Collection Process

Source: Texas DOT

For larger projects, TxDOT utilizes AASHTOWare Site Manager, including the Routine Maintenance Contract Administration module. Daily work reports allow inspectors to capture work performed at the job site such as personnel, equipment, work items, quantities, descriptions, etc. Over 3,700 pay items are used on routine maintenance contracts and the Maintenance Distribution Window, a custom upgrade to Site Manager, ties the pay item cost to the MMS function code (i.e., what work is being performed) and amount of work performed. The MMS then provides reports by function code for both in-house and contracted work and TxDOT actively monitors data quality to ensure accurate reporting and analysis” (Allen, et. al. 2023).

*Note: This practice example was derived from NCHRP Research Report 1076: A Guide to Incorporating Maintenance Costs into a Transportation Asset Management Plan.

- Chapters

-

Chapter 6

Sections - Chapter 6 Home Page

- Chapter PDF

Chapter 6

Quick Links

6.6.3

Incorporating Maintenance Costs into TAMP Analysis

This subsection introduces strategies for incorporating maintenance costs into key TAMP analyses, such as lifecycle planning, risk analysis, and financial/investment planning. It also provides insights into addressing unexpected disruptions using historical trends and other data. While many agencies capture maintenance costs and asset conditions within an MMS, few agencies use that data for the type of long-term analysis used to develop a TAMP.

Life Cycle Planning

One benefit of categorizing maintenance activities by their impact on the asset life cycle is that it facilitates incorporation of costs from those activities into Life Cycle Planning (LCP) analysis.

- Preventive Maintenance, Repair, and Unit Replacement costs are all critical inputs to LCP analysis. These costs are sometimes considered under the Preservation work type by State DOTs. Assets are typically eligible for each type of maintenance activity at a specific point in their lifecycles. Once a certain level of deterioration has been reached, a given type of activity ceases to be a cost-effective treatment. To incorporate these maintenance activities into LCP for a given asset class, agencies should consider the following:

-

- The size of the asset inventory.

- The number (or percentage) of assets eligible for the activity type.

- The length of time a typical asset is eligible for the activity type.

- The available treatments and their unit costs.

- How the application of each treatment impacts asset conditions.

- The quantity of each treatment to be applied in each year of the analysis.

- Operations, routine maintenance, and Organizational Strengthening costs do not have a direct impact on future conditions, and are generally not included in LCP analysis.

Risk Management

Maintenance crews and contracts are often critical components of risk mitigation strategies. The way these resources are deployed to address risks depends on the type of risk, which can be broadly incorporated into two categories: events and trends.

Risk Events

Maintenance resources represent a transportation agency’s first responders to major and minor disruptive events. Costs for response to risk events can be captured using normal work reporting procedures. Agencies often apply a code to signify if the work being reported is in response to a specific event. In some cases, the agency may be deploying maintenance resources in response to an event that has not yet been identified. In these cases, staff may need to review past records so they can be associated correctly.

Trends and Long-Term Change

Maintenance can be deployed to address long-term trends that impact asset conditions. Other trends may impact an agency’s ability to deploy maintenance. Examples of trends that impact maintenance include the following (Allen, et.al. 2023).

- Changes to regulations, requirements or standards may require a rapid response to replace non-conforming assets, or may impact the cost of future maintenance.

- Changing customer expectations may lead to changes in maintenance performance standards and drive future budget changes.

- Funding fluctuations may provide a boost to or decline in maintenance capabilities. In turn this could lead to changes in asset performance, or vulnerabilities.

- Aging infrastructure can lead to network wide changes in maintenance needs. This can occur cyclically, following large building cycles, such as the interstate construction era from 1960 to 1980.

- Staff turnover due to retirements can create a need for better knowledge management.

- Rapid system expansion can lead to an increased need for future maintenance. Since the need is not immediate, there can be a lag between the need arising and an awareness of that need among executives and legislators who establish maintenance budgets.

- Long-term or gradual environmental changes can impact asset performance by exposing infrastructure to conditions it was not designed to withstand. Maintenance may be required to retrofit or replace poorly performing assets.

Financial Planning

The TAMP Financial Plan should consider all sources of funding used to support maintenance. The Financial Plans should indicate how that available funding is expected to be used over the TAMP time period. This will typically require extrapolation or forecasting beyond established maintenance budgets. The maintenance activity categories can be helpful in determining how to account for this funding within the plan.

- Preventive Maintenance, Repairs, and Unit Replacements are often funded and delivered by multiple programs. As such some of these costs may be captured under the Preservation work type, and some captured under Maintenance. Agencies should take care in understanding how this work is funded and delivered to ensure costs are fully captured and not double counted in the TAMP.

- Funding for Operations and Routine Maintenance may come from its own budget line or be part of overall maintenance funding. Additionally, some operations expenses may be funded out of capital programming through programs such as the Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ) program. These activities are generally performed in a similar fashion regardless of asset condition. Therefore, these are commonly included as fixed-cost items that reduce the amount of funding available for activities that improve asset condition. Typically, this is included as an average annual cost.

- Organizational Strengthening activities can be budgeted separately from the other categories to clearly communicate their importance and show what activities are planned. These activities can be tracked using the time, labor, and material features in a maintenance management system.

A process for developing TAMP financial plans has been established through several documents. Most recently, NCHRP Report 1076, Guide for Incorporating Maintenance Costs into a TAMP updated this process to better incorporate maintenance costs (Allen et. al. 2023).

- Determine the scope of the TAM program.

- Identify maintenance fund sources.

- Establish maintenance fund uses.

- Structure maintenance sources and uses list.

- Validated the list.

- Document Constraints.

- Document assumptions about fixed costs.

Investment Strategies

As described in Chapter 5 of this guide, investment strategies establish a long-term plan for how the agency will apply its resources to achieve its asset management objectives. Agencies typically develop investment strategies through a scenario-based planning process. In this process the agency evaluates costs and benefits of different investment scenarios to choose the most appropriate. Since the majority of TAM funding comes through capital programming that has traditionally been the focus of investment strategy development, incorporating maintenance costs and benefits into this process may require incorporation of additional performance measures, such as those established through Maintenance Quality Assurance (MQA). MQA performance measures are often more directly related to investments in maintenance activities, whether through in-house crews or contracts. NCHRP Report 1076, Guide for Incorporating Maintenance Costs into a TAMP suggests the following steps for developing investment strategies that fully incorporate maintenance investments and benefits (Allen et. al. 2023).

- Define the role of maintenance in each scenario.

- Identify existing commitments to future investments in maintenance.

- Incorporate MMS and MQA data to improve predictions of future conditions.

- Perform initial budget allocations, including maintenance.

- Identify candidate projects and field crew capacity.

- Develop scenarios for analysis.

- Review predicted future conditions and predicted maintenance needs.

- Finalize funding levels by use.

- Document maintenance strategies for addressing performance gaps.

- Document assumptions and strategies.

Maryland DOT

The MDOT SHA reports labor, equipment, and materials costs for its State forces’ work into the electronic team activity cards (eTAC) system. These costs are captured by asset or unit. MDOT SHA enters contract data into the FHWA Financial Management Information System (FMIS) and other contract management software. The contract systems and eTAC assign a Project Cost Activity (PCA) code for each expense. The PCA codes allow the costs from similar work, delivered by different means, to be aggregated. The PCA codes are linked to the twenty-one Maryland Condition Assessment Reporting System (MCARS) elements to align costs with asset performance. MDOT SHA uses QlikView to aggregate the work output, cost data, and MCARS data and associate each to the appropriate PCA code for the work activity accomplished (see Figure 6-B, a screenshot of QlikView provided by MDOT SHA). Data aggregation with QlikView works well if data is accurate with the PCA codes, costs, and accomplishments.

Screenshot of QlikView

Source: MDOT SHA

This approach enables MDOT SHA to perform an analysis to determine whether in-house or contracted maintenance provides a more cost-efficient result for the activity or asset. This is an important analysis to consider when developing maintenance work programs as it allows an agency to be strategic with limited resources” (Allen, et. al. 2023).

*Note: This practice example was derived from NCHRP Research Report 1076: A Guide to Incorporating Maintenance Costs into a Transportation Asset Management Plan.

Texas DOT

TxDOT provides an example of effective contract maintenance cost data collection processes. TxDOT contracts approximately 52 percent ($620 million) of its $1.2 billion maintenance budget for routine maintenance. Contracted work is interfaced into TxDOT’s MMS in two ways: from its enterprise resource planning (ERP) software and from its construction contract management software. TxDOT typically uses work orders (WO) for contracts less than $25,000. The process for capturing and reporting contract maintenance costs is shown in Figure 6-A.

Figure 6-A: TxDOT Contract Purchase Order Data Collection Process

Source: Texas DOT

For larger projects, TxDOT utilizes AASHTOWare Site Manager, including the Routine Maintenance Contract Administration module. Daily work reports allow inspectors to capture work performed at the job site such as personnel, equipment, work items, quantities, descriptions, etc. Over 3,700 pay items are used on routine maintenance contracts and the Maintenance Distribution Window, a custom upgrade to Site Manager, ties the pay item cost to the MMS function code (i.e., what work is being performed) and amount of work performed. The MMS then provides reports by function code for both in-house and contracted work and TxDOT actively monitors data quality to ensure accurate reporting and analysis” (Allen, et. al. 2023).

*Note: This practice example was derived from NCHRP Research Report 1076: A Guide to Incorporating Maintenance Costs into a Transportation Asset Management Plan.